The amyloid-beta pathway: a key player in the pathogenesis of AD

For decades, clinicians have been unable to offer a treatment to slow the cognitive and functional decline of their patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Cholinesterase inhibitors are formulated to preserve memory by preventing acetylcholine breakdown, but these agents lose effectiveness as the disease progresses and less acetylcholine is produced.1 The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine has shown some clinical benefit in moderate-to-severe AD but no efficacy in early-stage AD.2

Investigators, however, have continued to search for answers, probing alternative treatment targets to attempt to slow or even halt AD’s debilitating effects. One such target, the amyloid-beta cascade, is in the forefront of research. Through this pathway, amyloid-beta proteins proliferate, aggregate and lead to amyloid plaques and, ultimately, tau tangles that diminish cognition and function. Newer agents on the market and in the pipeline have shown efficacy in mild-to-moderate AD by targeting this pathway and eliminating amyloid plaques, and these findings are providing patients and their families with new hope against a difficult-to-manage disease.

“It is essential to control amyloid-beta as the place to start to find the right therapy to prevent or treat dementia,” says Samuel E. Gandy, MD, PhD, Professor of Alzheimer’s Disease Research and Associate Director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

The amyloid-beta cascade

Researchers have been following the amyloid-beta pathway since the mid-1980s, when the protein and its amino acid sequence were strongly associated with Down syndrome and, soon after, AD.3 Through the 1990s and early 2000s, studies that focused on autosomal dominant AD genes, genetic risk factors for amyloid-beta accumulation and AD-related biomarkers, provided evidence that AD pathophysiology begins to develop decades before the onset of symptoms.3

“There are believers in this hypothesis, and there are disbelievers,” says Pierre N. Tariot, MD, Institute Director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix and Co-director of the International Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative. “The bottom line is that there is strong genetic evidence that amyloid is in some cases sufficient to cause Alzheimer’s dementia and in other cases necessary, but some say that this hasn’t been fully determined.”

What is known is that many people accumulate amyloid deposits in the brain as they age. As part of the normal molecular life cycle, the amyloid precursor proteins (APPs) from which amyloid-beta is developed are cleaved by alpha-secretase proteolytic enzymes, resulting in harmless amyloid fragments. Alternatively, some APPs are processed by gamma-secretase and beta-secretase enzymes, causing the resulting amyloid fragments to misfold and proliferate, leading to an imbalance in amyloid-beta production and breakdown common among people with AD.3

Misfolded amyloid-beta proteins initially are produced as soluble monomers; these monomers then proliferate and aggregate into larger soluble forms, including dimers and trimers, oligomers and protofibrils. Some of these aggregations later become insoluble fibrils that ultimately develop into insoluble plaques; both formations are associated with synaptic dysfunction in AD.3

Aside from proliferation, other factors that contribute to brain amyloid-beta buildup in AD include changes in receptor expression that dictate amyloid-beta movement between the brain and blood, as well as altered flow and absorption of cerebrospinal fluid during aging.3

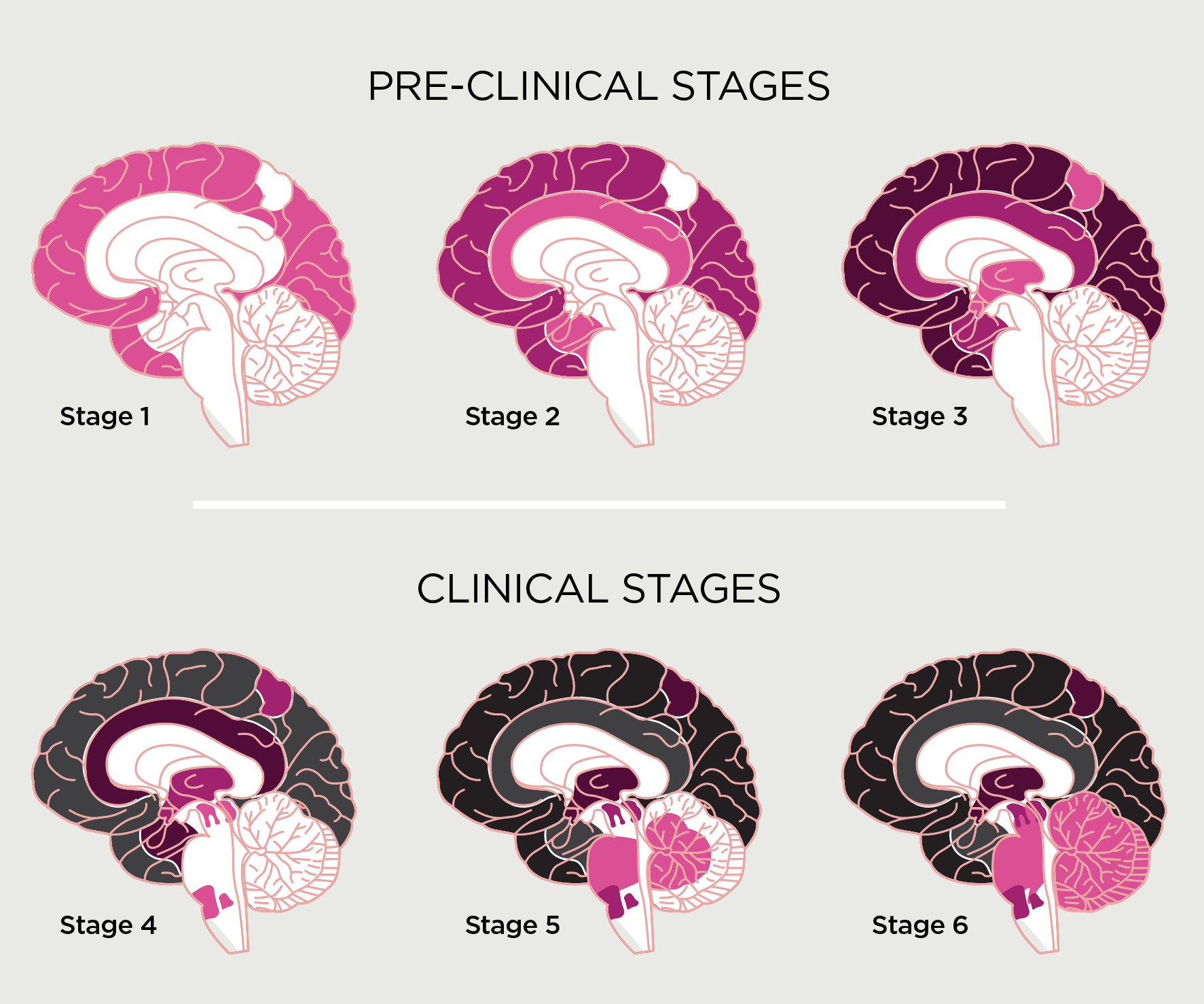

Plaque development and AD: decades in the making

As amyloid plaques keep developing and proliferating into an “amyloid bloom,” Dr. Tariot notes, they initiate the abnormal processing and accumulation of tau proteins and, ultimately, tau tangles. “It’s the tangle severity, not the amyloid burden, that is correlated with the degree of cognitive impairment in a patient who has symptoms,” he adds.

Through decades of investigation, researchers identified amyloid protein accumulation in the brain as an upstream process that begins decades before AD symptoms develop (see Figure 1). This has led investigators to hypothesize that if the amyloid-beta cascade and plaque production could be detected and disrupted, the progression of AD and its devastating effects could be delayed and perhaps halted.

Researchers have responded by developing agents formulated to disrupt specific segments of the cascade. Since 2016, several molecules have been created to either prevent amyloid proteins from aggregating or inhibit the beta-secretase and gamma-secretase enzymes that misfold amyloid proteins. But so far, neither mechanism of action has shown efficacy in slowing AD-related cognitive and functional decline.4

A novel approach to slowing progression

A more recent mechanism for disrupting the pathogenesis that leads to plaques has involved development of amyloid-targeting agents, synthetic monoclonal antibodies that interact with different aspects of the cascade and prompt the immune system to detect and destroy soluble and insoluble amyloid formations, including plaques. While earlier amyloid-targeting antibodies have not shown efficacy, more recently developed agents in this class have been shown in clinical trials to slow clinical progression of early-stage AD compared with placebo.5-8

“In an 18-month trial period, persons on one of these agents are likely to have about 5 to 6 more months of preserved higher level of functioning compared with patients not receiving the treatment,” Dr. Tariot says. “That is, patients receiving these agents are about a third better off after 18 months, and there is thinking that if the treatment were to be continued, that treatment difference might continue to increase over time.”

Adds Dr. Gandy, “The data on treatments targeting amyloid-beta are very encouraging. It is the most hopeful mechanism of action we have seen so far.”

Figure 1.

Stages of Alzheimer’s disease: amyloid-beta deposition over time3

Illustration by Juhee Kim

Illustration by Juhee Kim

Caution is necessary in certain patient populations

It is important to note that amyloid-targeting antibodies carry a risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which is the most common adverse effect of these agents. ARIA is believed to be caused by neuroinflammation or vascular rupture associated with plaque removal.9

ARIA is usually asymptomatic, but in some cases, it can cause headaches, worsening confusion, dizziness, visual disturbances, nausea and seizures.9 It is most commonly associated with edema (ARIA-E) or hemorrhage (ARIA-H); either subtype has been reported in about 40% of patients receiving these agents based on imaging tests, with one-quarter of patients reporting symptoms.10

Researchers also have found that ARIA-E is more prevalent at treatment initiation, at higher dosages, among patients with more than four microhemorrhages at baseline, and among patients who carry the ApoE4 gene.9 Therefore, genetic testing for the ApoE4 gene is strongly recommended before administering an amyloid-targeting antibody, Dr. Tariot advises. In addition, studies have found that the risk of ARIA-H increases with age and cerebrovascular disease.9

Illustration by John Holcroft / Ikon Images

Illustration by John Holcroft / Ikon Images

Promising studies continue to explore anti-amyloid therapies

Targeting the amyloid-beta cascade holds significant promise for AD treatment and is among the most common mechanisms of action of AD agents now in development. About 25 therapies targeting different aspects of the cascade are in various clinical trial stages, as are agents that target alternative pathways associated with AD pathophysiology such as inflammation, oxidative stress and synaptic function.11

Currently, anti-amyloid antibodies are administered by intravenous infusion, but subcutaneous formulations also are being developed. One subcutaneous molecule has received FDA fast-track designation,12 while others are in early-stage clinical trials. “This could be a major game-changer,” Dr. Tariot says. “Patients wouldn’t need to go into an infusion center. You could use an autoinjector at home.” He adds that, in addition to convenience, ease of use and cost-effectiveness, subcutaneous amyloid-targeting antibodies may reduce ARIA-E incidence compared with intravenous formulations, as peak drug levels would be lower with the subcutaneous versus the intravenous version.

Could AD be prevented?

As research into slowing AD progression continues, some investigators are turning their attention to stopping the disease before it develops. There are large clinical trials studying whether amyloid-targeting antibodies can prevent AD in people who are at known risk of the disease but who don’t yet have cognitive or functional symptoms.

For example, in one AD prevention trial, unimpaired participants ages 55 to 80 with elevated or intermediate levels of amyloid confirmed by brain imaging will receive an amyloid-targeting therapy or placebo to determine if the agent can prevent plaques and tau tangles from developing and thereby prevent AD in older persons at risk of the disease. Study completion is scheduled for 2027.13

In another AD intervention trial, unimpaired participants ages 55 to 80 who are at risk of developing AD based on blood biomarkers will receive an amyloid-targeting therapy or placebo to determine if the agent can prevent AD in older persons at risk of the disease. Study completion is also scheduled for 2027.14

Although previous AD prevention studies have not yielded clinically meaningful results, Drs. Tariot and Gandy say the concept still is worth exploring given the performance of amyloid-targeting antibodies in removing brain plaques in clinical trials. “Can you stave off the so-called downstream effects on tau and inflammation and membrane function and essentially arrest the disease course?” Dr. Tariot asks. “That’s an unknown, but we should soon be getting those answers.”

—by Pete Kelly

References

1. National Institute on Aging. How is Alzheimer’s disease treated? Updated April 1, 2023. Available at nia.nih.gov.

2. McShane R, et al. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(3):CD003154.

3. Hampel H, et al. The amyloid-β pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(10):5481-5503.

4. Huang L-K, et al. Clinical trials of new drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27(1):18.

5. Ramanan VK, et al. Anti-amyloid therapies for Alzheimer disease: finally, good news for patients. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2023;18:42.

6. National Institute on Aging. NIA statement on new anti-amyloid therapy. July 6, 2023. Available at nia.nih.gov.

7. Petersen RC, et al. Expectations and clinical meaningfulness of randomized controlled trials. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2023;19:2730-2736.

8. National Institute on Aging. NIA statement on new anti-amyloid therapy. July 17, 2023. Available at nia.nih.gov.

9. Withington CG, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with anti-amyloid antibodies for the treatment of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol. 2022;13:862369.

10. Salloway S, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in 2 phase and 3 studies. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(1):1-10.

11. Cummings J, et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2023. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2023;9(2):e12385.

12. Cummings J. Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies are transformative treatments that redefine Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Drugs. 2023;83(7):569-576.

13. The ahead-345 study. Available at clinicaltrials.gov.

14. The trailblazer-alz3 study. Available at clinicaltrials.gov.

Strategies for diagnosing mild cognitive impairment due to AD

For patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), time lost to diagnostic and treatment delays can mean loss of cognitive and everyday functioning. Diagnosing AD in its early stages is critical to forming a management plan that can preserve function for as long as possible and help patients and their loved ones plan for life with the disease.1

“The earlier the intervention, the more likely it is to succeed,” says Samuel E. Gandy, MD, PhD, Professor of Alzheimer’s Disease Research and Associate Director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), an age-related deficit of memory or thinking that does not affect daily functioning, can be the first warning sign that warrants an evaluation to establish whether AD is the cause.1 And though MCI is mild, it still can be distressing to both patients and their families.

“Often, patients with MCI are painfully aware that something is wrong, but they don’t know how to make sense of it,” says Pierre N. Tariot, MD, Director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix and Co-director of the International Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative. “They don't know what’s going on. They don't know how serious it is, how much to worry. And their loved ones are worried.”

But it can be a challenge to differentiate AD from the myriad other potential causes of MCI—from medical conditions and adverse drug effects to mental illness, vitamin deficiency and more.2 Constraints on providers’ time and an underlying view of MCI symptoms by both patients and providers as a “normal part of aging” also can hinder early AD diagnosis.1

Fortunately, the road to identifying AD is becoming clearer, thanks to increased emphasis on the role of biomarkers—in particular amyloid-beta—in AD pathophysiology, combined with advances in detecting amyloid-beta before AD reaches its advanced stages or even develops. “Biomarkers are now essential to AD diagnosis,” Dr. Gandy says.

Revised guidelines in development

Researchers have been homing in on the amyloid-beta cascade as a major culprit in AD development, and this hypothesis has paved the way for treatments that have shown efficacy in slowing cognitive and functional decline in AD. The hypothesis also has fueled a drive toward earlier AD diagnosis by detecting amyloid-beta deposits before they form plaques and, ultimately, the tau tangles associated with AD-related dysfunction.3

Because the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association recognize the potential biological causes of AD, they are revising criteria for diagnosing and staging the disease based on existence of both biomarkers and cognitive and functional changes. The new recommendations will define AD as a biological disease rather than a clinical syndrome and present the disease course as a clinical continuum that begins with the appearance of biomarkers before AD symptoms surface.4

Under the new criteria, AD no longer would be classified as mild, moderate or severe, but in stages similar to the staging system used for cancer diagnosis and management. Based on symptoms and level of amyloid-beta proliferation, patients with AD would be staged from 0 (biomarkers portending future AD, but currently asymptomatic) to 7 (severe AD symptoms). The system also includes 4 biological stages, from A to D, indicating extent of biomarker proliferation.5 Currently, the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup is revising a draft of the guidelines based on scientific input. For updates, visit aaic.alz.org/nia-aa.asp.

The diagnostic journey

The road to MCI diagnosis typically begins at the primary care physician’s office, when either the patient or family members express concern about memory loss or “fogginess” or if the provider notices changes such as loss of insight. This is where physicians need to start suspecting MCI and its potential causes.1 “I think it’s just a matter of providers having the confidence to do the evaluation a few times and realize that they can go through a relatively simple pathway,” Dr. Tariot says (see Figure 1). He and Dr. Gandy describe the steps as follows:

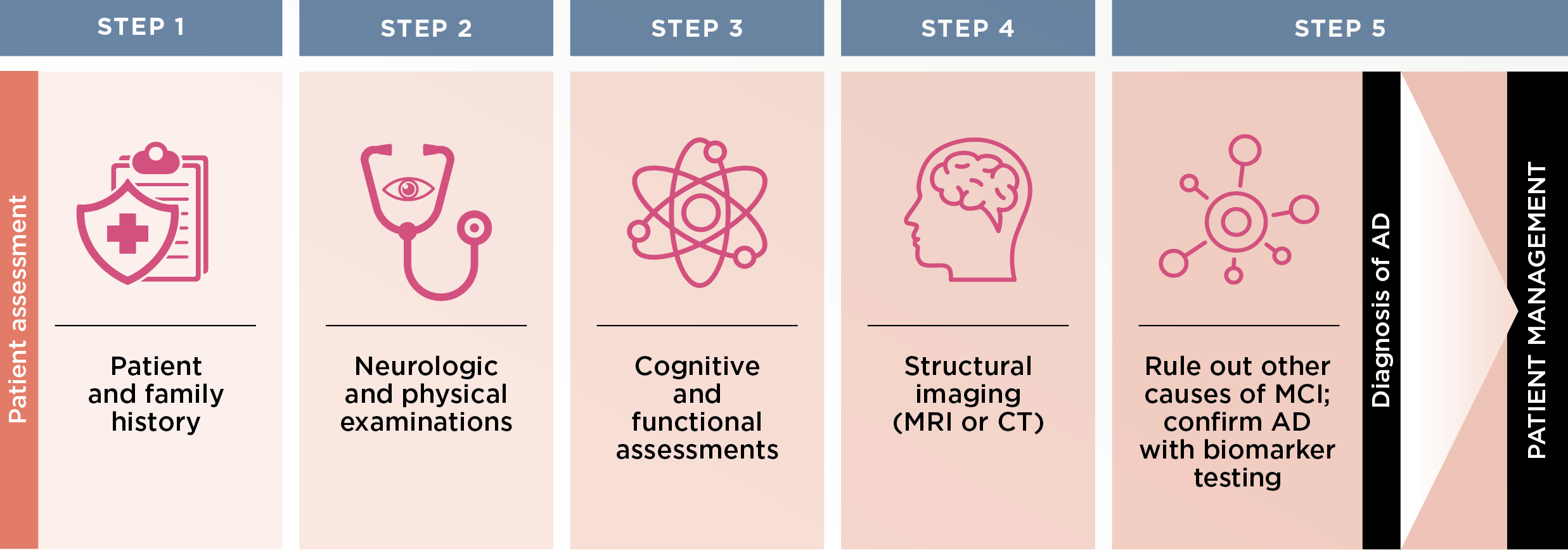

Figure 1.

Steps for diagnosing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD)1,2

STEP 1

Upon clinical suspicion or patient/family concern, perform a thorough patient history to look for past or current illnesses, medications and other risk factors for MCI, Drs. Gandy and Tariot advise. It is critical to have a family member or other knowledgeable caregiver to supplement the history, if possible. Also take a detailed family history, in particular to learn if family members had Parkinson’s- or AD-related dementia or other dementias.

STEP 2

Next is a structured neuropsychiatric examination, during which providers should watch for lapses in cognition during the interview and focus on neurological findings that could suggest an alternative etiology for MCI, such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, vascular dementia or sensory impairment, Drs. Gandy and Tariot advise. Routine lab tests also are necessary.

STEP 3

Equally critical to the examination is gauging the extent and severity of cognitive impairment, and numerous objective assessment tools are available. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment tool (MoCA) is one of the more comprehensive yet easily administered evaluations for assessing cognition, Drs. Gandy and Tariot say. The MoCA assesses a range of cognitive abilities, including orientation, short-term memory, executive function, language, abstraction, attention, naming and spatial relations.

A MoCA score between 18 and 25 typically suggests MCI, with lower scores indicating more severe impairment. However, any score of 21 or lower should be concerning, Dr. Gandy says.

For assessing function, the AD8 or Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ) are effective tools, Dr. Tariot says. Either assessment can be administered in a busy primary care setting in 10 minutes or less.

STEP 4

Then, routine structural brain imaging with unenhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or, if MRI is contraindicated, computerized tomography (CT) is required to assess for structural or other neurological abnormalities.

STEP 5

Next, rule out other causes. “The next step then is to understand what we’d be looking for and to consider what sorts of culprits can cause mild cognitive impairment and need to be ruled out,” Dr. Tariot says. While many cases are due to slowly emerging AD,1 he adds that other identifiable and reversible or more treatable conditions could instead be to blame. These include brain trauma, infection, mental illness (e.g., anxiety, depression), metabolic dysfunction (e.g., type 2 diabetes, hypothyroidism), neurologic disorder (e.g., vascular dementia) and toxin exposure.

Finally, confirm with biomarker testing. If AD is suspected after all other causes have been ruled out, an amyloid positron-emission tomography (PET) scan or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing can confirm the existence of amyloid-beta brain deposits and confirm the AD diagnosis. While Drs. Gandy and Tariot say either test modality is effective, they note that CSF testing is slightly more sensitive. “You pick up around 10% more patients with subtle elevated brain amyloid that you might miss with an amyloid PET scan,” says Dr. Tariot, adding that CSF testing also measures existence of tau proteins, which also can help establish the presence of AD pathology. Also consider CSF testing when clinical features such as hallucinations or amnesia might point to specific diagnoses, Dr. Gandy says.

However, third-party payers often dictate the choice of testing modality, and scanning with amyloid PET, which entails use of specific radiotracers sensitive to amyloid proteins, has shown effectiveness in detecting brain amyloid plaques indicative of early- or later-stage AD. In one study that followed 11,409 patients with MCI or dementia, amyloid PET scans were instrumental in ruling out AD in patients misdiagnosed with the disease and in diagnosing AD among patients in whom the disease had been missed.6

Blood-based biomarker testing (BBBM) is under investigation as a testing option for amyloid-beta presence. Data are insufficient to support widespread use of BBBM as a standalone AD screening test,7 but it could be used to confirm the need for CSF testing or amyloid PET scan. “If the blood test is definitively negative, we’re done for now,” Dr. Tariot says. “If it’s positive, let’s confirm that result with a spinal test or a PET scan.”

When the diagnosis is MCI due to AD: next steps

If amyloid PET or CSF testing indicates AD, it’s time to discuss disease management options. The discussion should start with a review of how to cope day-to-day with MCI, then move to the potential benefits and risks of available treatments, in particular the newer amyloid-targeting antibodies that have shown efficacy in destroying brain amyloid plaques and slowing cognitive and functional decline, Drs. Gandy and Tariot suggest.

Most importantly, now that early-stage AD has been diagnosed, both the patient and their family can now be armed with information to help maximize their future quality of life.

“If I were a patient, I’d have a better idea of what lies ahead,” Dr. Tariot says. “I can tell my loved ones and doctors how I want my future care plan to be if I deteriorate. I and my loved ones can be counseled as to what I’m living through now, how to cope with it better, how to mitigate things in a practical day-to-day sense, how to communicate a little differently…it’s important to identify and evaluate a person with mild cognitive impairment and render as clear a diagnosis as possible.”

—by Pete Kelly

References

1. Porsteinsson AP, et al. Diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease: clinical practice in 2021. J Prev Alz Dis. 2021;3(8):371-386.

2. National Institute on Aging. What is mild cognitive impairment? Available at Alzheimers.gov.

3. Hampel H, et al. The amyloid-b pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(10):5481-5503.

4. Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. NIA-AA Revised Clinical Guidelines for Alzheimers. Published July 15, 2023. Available at aaic.alz.org/nia-aa.asp.

5. Steenhuysen J. Alzheimer’s diagnosis revamp embraces rating scale similar to cancer. Published July 16, 2023. Available at reuters.com.

6. Rabinovici G, et al. Association of amyloid positron emission tomography with subsequent change in clinical management among Medicare beneficiaries with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. JAMA. 2019;321(13):1286-1294.

7. Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. Alzheimer’s Association Global Workgroup releases recommendations about use of Alzheimer’s “blood tests.” Published July 31, 2022. Available at aaic.alz.org.

Helping patients and care partners cope with a diagnosis of early AD

Receiving a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) comes with a devastating emotional impact. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, when a person hears the news early in their journey, they become aware of their impending decline, and they may experience grief, anger, fear, shock, disbelief and more.1-3 And while the patient is dealing with these complex emotions, so too are their care partners, the preferred term at this stage, says Valerie T. Cotter, DrNP, AGPCNP-BC, FAANP, FAAN, “especially in MCI due to early AD when the person doesn’t need a caregiver but someone who will partner with them,” says Cotter, who is Associate Professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing and School of Medicine in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences and a nurse practitioner in the Memory and Alzheimer’s Treatment Center.

In addition to facing years of providing support in a way they might never have anticipated, care partners must also process the fact that the affected person will likely lose their memories of them while also experiencing personality changes that may render them unrecognizable. Adding to the care partner’s challenge is that AD may impair the person’s ability to process emotions, according to some experts, making it tougher to know how to provide the best support.2

However, as a clinician, you have the opportunity to make a positive impact on the patient’s care by providing support through this period of acceptance and planning. “I think it’s really important that the clinician not only think about pharmacologic interventions but especially think about psychosocial interventions,” says Cotter. In her practice, she has found several strategies that can help ease the transition for patients and their loved ones. Here, she offers insight on how to provide them with psychosocial support.

Make it a team effort

It’s crucial for anyone with a cognitive impairment diagnosis to have care partners at home who can not only support them through their diagnosis but also in their day-to-day lives as their capabilities shift. “Our schedulers encourage new patients to come in to the office with what we call a ‘knowledgeable informant,’ whether an adult child or a spouse or friend,” explains Dr. Cotter. If they don’t have anyone who can make it, she says, “I always ask them, ‘Who else can I talk with on the phone after the appointment to learn more about you and how you’re doing?’ ”

That knowledgeable informant will then become an ongoing partner in their care. And in the early stages, it’s just as important to keep that person informed as the patient so they know what’s ahead. When people don’t have someone to call on or live far away from loved ones, Dr. Cotter points them to a Geriatric Care Manager, a nurse or social worker who can help identify needs and identify solutions to meet them.

As for providing background and education to get them started down the path to understanding what’s ahead, if a practice doesn’t already have pamphlets with the basics and places to get more support and information, Dr. Cotter recommends both patient and care partners turn to the Alzheimer’s Association for education, support, and to connect with other families in their circumstances.

Reframe the discussion

The burdens that come along with this diagnosis can be substantial, but Dr. Cotter says reframing how you talk about it to focus on their future can have a positive impact. “I try to help people understand that even though it is a devastating diagnosis, there’s always hope around having a good quality of life for a long time because people can live for years with Alzheimer’s disease.”

While she can’t promise it will be easy, she also emphasizes that there can still be enjoyment. When it comes to planning, she says, “We’re going to do the best we can to help maintain your function and quality of life through these stages.” She finds this reframing helps both patients and the people around them feel less helpless when they’re coming to terms with the challenges they’ll be facing.

Encourage “planning while you can”

Dr. Cotter says processing a future of reduced function can be especially tough. “Everyone wants to maintain the level of independence that they’ve always had,” she says. But when it comes to big and little to-dos like household chores, cooking, grocery shopping, etc., “in the early stages, the patient and their care partner really need to think about how that’s going to change and who will get those things done.” She also says having a driving evaluation in the early stages is important. “You don’t want to wait until there’s a problem with them getting lost or having an accident before it’s recognized,” she warns.

And on a larger scale, she explains, “It’s crucial to discuss financial implications, power of attorney and advanced directives.” She says she tells her patients they need to consider “Who’s going to help me with those things when my disease progresses and I can no longer do them by myself?” while they are still able to understand the impact and help get rid of the unknowns.

While this is important for logistical reasons, it’s equally important to help soothe the anxiety around the what-if’s—not only for the patient, but also for their support system. Dr. Cotter says participating in the planning stage can help make all parties involved feel a bit more in control and ready for what’s to come.

Promote stimulating activities

While having a daily routine can be helpful in getting patients with impaired memory through each day smoothly, Dr. Cotter is adamant about making sure patients have stimulation in their lives. She says patients dealing with dementia “can get really bored, and because they lack the initiative or motivation or organization, they sit in front of the TV all day long—that’s not good.” She continues, “So developing a routine where there’s daytime activity with physical, social and mental stimulation during the day and then an adequate six to eight hours of sleep every night is key.”

One thing she finds to be helpful: Adult day programs, community-based programs where patients go a few times a week. They have professional staff there with nurses and social workers, and they do a full assessment of the patient and help engage them in activities that fit their capabilities and interests.”

Providing stimulation is not merely a way to help people with dementia pass the time in more engaging ways: According to research published in Germany, psychosocial interventions can have big positive impacts. For example, cognitive stimulation and cognitive training improve cognitive abilities, activity planning and reminiscence can enhance emotional well-being, and aromatherapy and music therapy can reduce behavioral symptoms. Art programs have also been shown to improve quality of life and feelings of well-being.4-6

Meet them where they are

Denial is commonly reported in the newly diagnosed, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Nonetheless, Dr. Cotter finds that with cognitive decline it’s important not to force anything but rather meet the patient where they are. She says when family members talk of seeing denial in the patient, there may be something else at play. “My experience has told me that the family sees it as an active form of denial, when really it may be a decreased capacity to process and understand their condition.”

Her strategy in this situation? While she goes over the information about their diagnosis at the first encounter, if the patient doesn’t seem to be grasping it at future visits, she turns the focus to what they may be experiencing instead. “It’s a lot more palatable to describe their condition related to symptoms. They may have trouble with words, and there’s stigma with the diagnosis—it can cause anxiety and agitation if you keep pushing it,” she says. “You have to follow the lead of the person who is experiencing it and how much they are going to be able to remember what you tell them.”

Denial on the part of care partners is much more worrisome, says Dr. Cotter, as they’ll need to understand the importance of their role in keeping their loved one safe. In that case, she spends more time educating them, listening to their concerns, and—most importantly—pointing them toward support.

—by Beth Shapouri

Strategies for care partners as their loved one’s disease progresses6,7

Family members and other care partners will need guidance to help them adjust to their loved one’s diagnosis and the changes ahead. First, it is crucial to provide them with the name and contact information for a social worker who can answer questions and offer resources throughout their journey. And while care partners can understandably be overwhelmed by increasing responsibilities, these everyday strategies may ease some of the burden:

- Keep things simple. Focus on communicating one thing at a time.

- Encourage a daily routine so the person knows when and how certain things will happen.

- Reassure the person that they are safe and you are there to help.

- Focus on their feelings. For example, say, “You seem worried.”

- Don’t argue with the person or show your frustration or anger.

- Use humor when you can.

- Take the person for a walk or find them a safe place to walk if they are restless or tend to pace.

References

1. Alzheimer’s Research Association. How To Deal With Your Patient’s Emotional State After Alzheimer’s Diagnosis. Available at alzra.org.

2. da Silva RCR, et al. Deficits in emotion processing in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2021 Jul-Sep;15(3):314-330.

3. Pietrzak RH, et al. Amyloid-β, anxiety, and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: a multicenter, prospective cohort study.” JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Mar;72(3):284-91.

4. Kurz A, et al. Psychosocial interventions in dementia. Neurologist (Nervenarzt). 2013 Jan;84(1):93-103.

5. Deshmukh SR, et al. Art therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Sep 13;9(9):CD011073.

6. National Institute on Aging. Managing Personality and Behavior Changes in Alzheimer’s. Available at nia.nih.gov.

7. Kumar A, et al. Alzheimer’s disease (Nursing). StatPearls [internet]. June 5, 2022.

Case Study

PATIENT: MARTIN, 69, HAD A HISTORY OF EARLY ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE (AD) AND MILD HYPERTENSION.

“Martin’s scans confirmed a slowing of his early AD”

PHYSICIAN:

Anne-Marie Osibajo, MD

Behavioral neurologist and neuropsychiatrist, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City

Treatment history:

About 5 years ago, when he was 64, Martin’s family noticed that he kept repeating questions and forgetting basic things, like what they had for dinner or the date and time of his grandson’s soccer game. This was highly unusual for someone who had been an investment banker. In fact, as Martin’s forgetfulness worsened, he was asked to resign from his position because he had been making a series of mistakes, such as failing to execute trades or provide his clients with important paperwork.

When I first saw Martin more than a year ago, his wife told me he was constantly misplacing his wallet and glasses, to the point where he would stick multiple written reminders around the house, on countertops, doors and windows—even in the refrigerator. When that didn’t work, he became increasingly frustrated, anxious and, occasionally, depressed. Tasks and activities that he used to enjoy, such as planning family vacations, were nearly impossible to complete.

Initiating treatment:

Given his symptoms and his age, Martin was a good candidate for a novel therapy being studied in clinical trials, lecanemab, an injectable drug that targets the harmful buildup of beta-amyloid plaques in the brain. (The FDA recently approved lecanemab for patients with mild dementia and other symptoms of early AD.) Martin’s eligibility for the drug was confirmed by his Montreal Cognitive Assessment score of 22, and by the presence of mild amyloid plaques on an amyloid PET scan, which is indicative of mild cognitive impairment due to AD. Conditions like Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia or Parkinson’s disease were ruled out.

Martin was initially hesitant to receive an infusion, but when I discussed the potential benefits of lecanemab—most notably that it might delay the progression of his early AD—he agreed to try it. Side effects of the drug are usually mild, and include headaches, dizziness and fever, but they generally pass within a few weeks. We also discussed possible major side effects, notably amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), commonly marked by edema or hemorrhage (for more on ARIA, click here). As for Martin, he had no major complaints about the biweekly infusions. He also received sertraline as treatment for his anxiety and depression.

More than a year later, two follow-up MRIs 6 months apart have confirmed that the there were no significant changes in the brain size and amyloid PET scan revealed that the amount of amyloid plaques in Martin’s brain had not increased. Not only has the progression of his early AD slowed, but even though he still has memory challenges, the impairment has not worsened. And while Martin never did return to work, he’s doing some general consulting for his son-in-law’s accounting firm, which has boosted his self-esteem and greatly lessened his anxiety.

Considerations:

Anti-amyloid therapies are disease-modifying agents that are currently approved for MCI due to AD and mild AD dementia. Studies have shown they slow progression of the disease by 5 or 6 months in most patients and possibly even longer in Martin’s case. Gaining back that time was especially important for Martin because he had always intended to travel in retirement and spend more time with his grandkids.

Like Martin, your patients with memory impairment independent of normal aging or a heart condition, as well as their families, will likely want to maximize the time they have before AD seriously interferes with their functioning. For people like Martin who are otherwise in good health, anti-amyloid agents offer a clinically meaningful path toward making those precious moments possible.

KOL on Demand

Q&A

Expert insight on managing Alzheimer’s disease

OUR EXPERT

Nicole Purcell, DO, MS,

Neurologist, Senior Director,

Clinical Practice,

Alzheimer’s Association

Getting to the bottom of MCI

Q: When you suspect a patient has mild cognitive impairment, what steps do you take to confirm the diagnosis and potentially uncover an underlying cause?

A: Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is characterized by subtle changes in memory and thinking serious enough to be noticed by the affected person and their close family and friends but not severe enough to disrupt their ability to carry out everyday activities. MCI is often mistakenly accepted as a “normal” part of aging, yet it is not normal or even typical. In fact, it’s estimated that 12% to 18% of people age 60 or older have MCI. While some individuals with MCI revert to normal cognition or remain stable, studies suggest 10% to 15% of individuals with MCI go on to develop dementia each year. About one-third of people with MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease will develop clinical dementia within 5 years.

Although a physician may suspect MCI because of patient-reported symptoms, no test can provide a definitive diagnosis. So doctors must rely on other means, such as a review of the patient’s medical history, patient questionnaires, clinical exams and brief assessments to evaluate memory and thinking. Things they look for include changes in reasoning, problem-solving, planning, naming and comprehension.

Sometimes, an MCI diagnosis requires ruling out other systemic or brain diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies (associated with rapid eye movement sleep abnormalities), cerebrovascular disease in the blood vessels that support the brain, or prion disease or cancer (characterized by more rapid cognitive decline).

For MCI due to Alzheimer’s, guidelines recommend finding a biomarker that indicates changes in the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and/or blood that are caused by physiologic processes associated with Alzheimer’s pathology. Unfortunately, not all physicians and patients have easy access to biomarker testing methods.

Benefits of early AD diagnosis

Q: Why is it important to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease early and how would you confirm the diagnosis?

A: Early detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias is critical because it offers the best opportunity for care, management and treatment. It also provides diagnosed individuals and their caregivers more time to plan for the future, adopt lifestyle changes that may help slow disease progression, participate in clinical trials and enjoy a higher quality of life for as long as possible.

It also gives diagnosed people the opportunity to express their wishes about legal, financial and end-of-life care decisions as well as to address potential safety issues, such as driving or wandering, before a crisis occurs.

While there is still no cure for AD, the advent of two new FDA-approved treatments proven to delay progression drives home the importance of early detection and diagnosis. The reason: They are only available to individuals in the earliest stages of the disease. What’s more, as therapies continue to be developed, early and accurate diagnosis will help determine eligibility for current and future treatments.

To confirm an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, clinicians can collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) via a spinal tap or perform special PET scans to detect beta amyloid and tau in the brain—two hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Less expensive and less invasive blood tests are in development but not yet ready or FDA-approved for clinical use.

Looking for changes

Q: For patients with early- to mid-stage AD, what type of personality changes are common and how can they be addressed by a healthcare provider and/or caregiver?

A: Depression is common among people in the early and middle stages of AD. It can be triggered by the trauma of receiving a fatal disease diagnosis, recognition that one’s memory and thinking are declining, loss of independence or feelings of guilt that the person is or will become a burden to their family.

However, identifying depression in someone with AD can be difficult as it shares some of the same symptoms as dementia, including apathy, loss of interest in activities and hobbies, social withdrawal, trouble concentrating and impaired thinking. As a caregiver, if you see signs of depression, discuss them with the primary doctor of the person with dementia. Proper diagnosis and treatment can improve the person’s sense of well-being and function. Medications or lifestyle interventions such as exercise, improving diet or sleep, or increased social activity are common treatment options.

As AD and other dementias progress, a person may exhibit dementia-related behaviors such as anxiety, agitation, and, in some cases, aggression. It is important for caregivers and others to recognize that these behaviors are not intentional; they are disease-related.

The key during any stage of the disease is to meet people where they are. Alzheimer’s affects individuals differently. The goal should always be to provide “person-centered” care that is grounded in knowing the person. Knowing a person’s likes, dislikes and preferences can help caregivers better understand what is triggering the behavior so you can take steps to address it in a way that is responsive to the individual.

Clinical Minute:

Special thanks to our medical reviewer:

Samuel E. Gandy, MD, PhD, Professor of Alzheimer’s Disease Research and Associate Director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York City

Maria Lissandrello, Senior Vice President, Editor-In-Chief; Lori Murray, Associate Vice President, Executive Editor; Lindsay Bosslett, Associate Vice President, Managing Editor; Joana Mangune, Senior Editor; Erica Kerber, Vice President, Creative Director; Jennifer Webber, Associate Vice President, Associate Creative Director; Ashley Pinck, Art Director; Sarah Hartstein, Graphic Designer; Kimberly H. Vivas, Vice President, Production and Project Management; Jennie Macko, Associate Director, Print Production

Dawn Vezirian, Senior Vice President, Financial Planning and Analysis; Tricia Tuozzo, Sales Account Manager; Augie Caruso, Executive Vice President, Sales & Key Accounts; Keith Sedlak, Executive Vice President, Chief Commercial Officer; Howard Halligan, President, Chief Operating Officer; David M. Paragamian, Chief Executive Officer

Health Monitor Network is the leading clinical and patient education publisher in neurology and PCP offices, providing specialty patient guides, clinician updates and digital screeens.

Health Monitor Network, 11 Philips Parkway, Montvale, NJ 07645; 201-391-1911; customerservice@healthmonitor.com.

©2024 Data Centrum Communications, Inc.

NAJ24-CU-AZ-1QEL