Pharmacotherapy update:

A new oral agent

for plaque psoriasis

The FDA approval of deucravacitinib, a first-in-class TYK2 inhibitor, represents a breakthrough that offers providers an effective and safe first-line option for moderate-to-severe disease.

—by Alex Evans, PharmD

With the recent approval of deucravacitinib, clinicians now have a new targeted treatment in their arsenal. The first in a novel class of tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitors,1 the oral medication represents a significant and exciting addition to existing treatments. As Bruce Strober, MD, Clinical Professor of Dermatology at Yale and Central Connecticut Dermatology notes, “It is a breakthrough oral medication with no laboratory monitoring requirements and more narrow effects in blocking inflammation,” he says. “Deucravacitinib will give providers another first-line option for psoriasis patients needing systemic therapy and who fail to respond to, or are unable to use, topical therapies.”

Targeted therapy with a novel mechanism of action

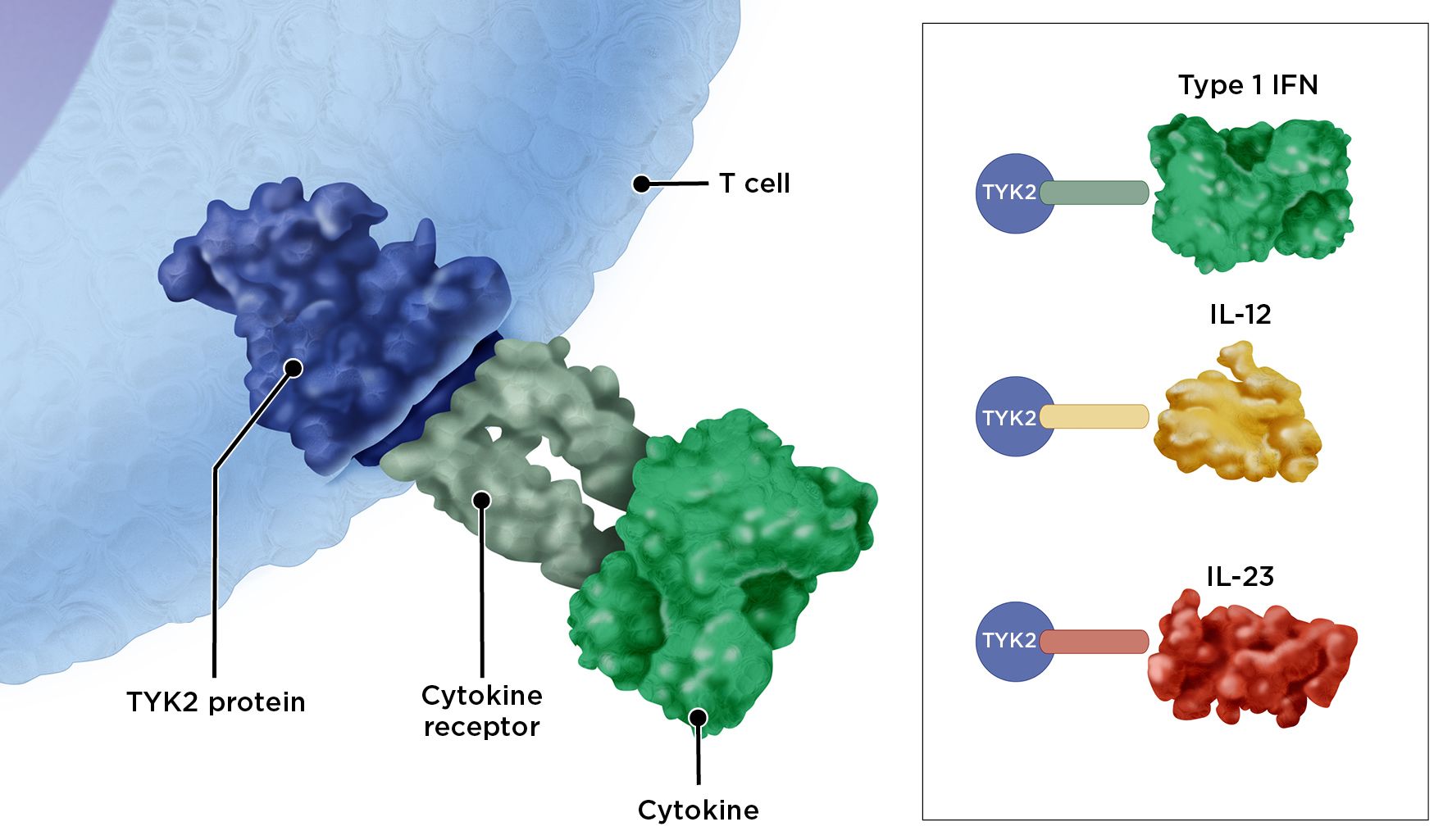

TYK2 is in the Janus kinase (JAK) enzyme family, along with JAK1, JAK2 and JAK3. These enzymes bond together in different pair combinations to produce a wide variety of effects throughout the body, including promoting the chronic inflammation found in plaque psoriasis, but also to carry out many other important biological functions. Leptin, growth hormone and erythropoietin all rely on JAK enzymes to exert their effects, but of the entire JAK family, TYK2 is mainly involved in chronic inflammation.2

As an inhibitor of TYK2, deucravacitinib blocks inflammatory cytokine signals that influence the immune system without affecting JAK pathways that have more broad systemic effects (see Figure 1, below). Apremilast, the only other oral targeted agent approved for plaque psoriasis, works by targeting PDE4, an enzyme involved in both inflammatory and immune responses.3

Figure 1. Deucravacitinib: First-in-class TYK2 inhibitor with a novel mechanism of action

Targets TYK2, thereby inhibiting key

inflammatory cytokines

Illustration by Suzanne Ghuzzi Silva

Illustration by Suzanne Ghuzzi Silva

Superior to apremilast

The POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 trials were double-blind, randomized phase 3 trials comparing deucravacitinib 6 mg per day with apremilast 30 mg twice daily and placebo for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Primary outcomes were 75% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) scoring and static Physician’s Global Assessment Score (sPGA) of 0 or 1, indicating psoriasis was clear or almost clear.1,4 Afterward, patients were able to enroll in the open label, long-term extension (LTE) trial.5

In both PSO-1 and PSO-2, patients responded better to deucravacitinib than apremilast or placebo. In PSO-1, 58.4% met PASI 75 goals at Week 16 in the deucravacitinib arm compared with 35.1% in the apremilast arm, and 53.6% met sPGA goals in the deucravacitinib arm compared with 32.1% in the apremilast arm. Similar results were found in PSO-2, and in both trials positive responses and superior efficacy over apremilast were maintained through 52 weeks.1,4 The LTE trial demonstrated continued deucravacitinib efficacy for up to a total of 2 years.

The most common adverse effects with deucravacitinib were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection. In PSO-1, serious adverse events as well as discontinuation due to adverse events were lower with deucravacitinib than with either apremilast or placebo.4 A similar safety profile was found in the PSO-2 and LTE trials for up to a total of 2 years.5

Proven efficacy with fewer side effects

The take-home message for clinicians: The findings of the POETYK clinical trials are exciting, not only because they confirm a new treatment option, but also because they demonstrate the superior efficacy of deucravacitinib over apremilast, its favorable safety profile and no need for laboratory monitoring requirements. In addition, deucravacitinib solely blocks TYK2 signaling in the immune system without affecting the many pathways mediated by JAK enzymes, some of which have systemic effects beyond immunomodulation (for example, those affecting blood cell development).

Dr. Strober summarizes the significance of TYK2 inhibition: “The clinical trial data of patients treated for up to 2 years with deucravacitinib show low rates of serious infections, major adverse cardiovascular events, malignancies, venous thromboembolism and herpes zoster. If these findings are replicated in a real-world setting, it would indicate deucravacitinib is associated with a lower rate of adverse events than other oral therapies.”

Insight on the approval of a first-in-class oral medication

The FDA approval of deucravacitinib in September 2022 offers a significant addition to the treatment options for patients with plaque psoriasis. Here, Bruce Strober, MD, Clinical Professor of Dermatology at Yale and one of the researchers for the POETYK PSO-1, PSO-2 and LTE trials, discusses what the trial data show and what the new approval means for clinical practice.

1. What is the significance of the approval of deucravacitinib and the availability of another targeted oral agent?

Deucravacitinib represents a breakthrough oral medication for plaque psoriasis patients. It demonstrated superior efficacy to apremilast in head-to-head trials, and its once-daily dosing is convenient for patients. In addition, it does not require any laboratory monitoring and also demonstrated an excellent safety profile compared with many existing therapies. These features may allow deucravacitinib to be an easier approach to treating psoriasis for both patients and dermatologists.

2. What does the data say about the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib vs. other available treatment options?

Deucravacitinib demonstrated efficacy that exceeds that of apremilast (via direct head-to-head study) and methotrexate (via indirect comparison). Based on the current trial data, it appears to have a similar efficacy as older injectable biologics, such as those targeting TNF-alpha, but does not appear to have the same efficacy typically seen with newer biologics targeting IL-23/IL-17, although this hasn’t been studied in direct clinical trials.

Overall, deucravacitinib was well tolerated in clinical trials. There was an increased risk of nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infections, but at this time no laboratory monitoring is required.

3. Which patients are good candidates for deucravacitinib?

Deucravacitinib can be considered for psoriasis patients who fail to respond to, or are unable to be treated with, topical therapies. Another group that would be ideal for deucravacitinib therapy includes patients who prefer oral medications to injectables. The evidence to date does not indicate any contraindications to the use of deucravacitinib, with the exception of patients who are immunocompromised or who have active infections. Some providers may want to also consider avoiding its use in patients with a history of malignancy.

4. What else should clinicians consider when prescribing this medication?

If a patient develops an active infection while using deucravacitinib, they might need to briefly discontinue the medication while the infection is being treated. Vaccinations might necessitate brief pauses in treatment also, although the data aren’t clear on this issue and it might depend on the type of vaccine.

Key factors to consider when choosing a targeted psoriasis treatment6-9

Patient characteristics

- Age, sex, body weight, psychosocial issues

- Patient expectations

- Comorbidities that may contraindicate or raise a caution on the use of certain injectable biologics (e.g., latent tuberculosis, severe heart failure, personal history or strong family history of demyelinating disease or alopecia areata for

TNF inhibitors, inflammatory bowel disease for IL-17 inhibitors) - Presence of concomitant diseases that may benefit from the same treatment (e.g., psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis)

Disease characteristics

- Disease severity, activity and stability

- Skin areas involved

- Severity of symptoms (e.g., pruritus)

- Disease and treatment history, rapid relapse after treatment withdrawal, intermittent or continuous disease activity

Treatment-related considerations

- Overall efficacy (short- and long-term) and the need for a rapid response

- Tolerability and safety (including patient concerns about side effects and the need for laboratory monitoring)

- Need for flexible treatment (e.g., need for easy interruption or restart of therapy)

- Dosage and administration (dosing schedule; oral, subcutaneous, intravenous)

References

1. Warren R, et al. Deucravacitinib, an oral, selective tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: 52-week efficacy results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 trials. SKIN. 2022;6(2).

2. Kvist-Hansen A, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with JAK inhibitors: A review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):29-42.

3. Li H, et al. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1048.

4. Armstrong AW, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jul 9]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;S0190-9622(22)02256-3.

5. Warren RB et al. Deucravacitinib long-term efficacy and safety in plaque psoriasis: 2-year results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO program. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:841.

6. Reich K, et al. Integrating new psoriasis therapies in the current treatment landscape. Eur Med J. 2018;3(1):22-29.

7. Drugs for psoriasis. Medical Letter Drugs Ther. 2019;61(1574):89-98.

8. Menter A, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029-1072.

9. Menter A, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486

Managing comorbidities

of plaque psoriasis

These strategies can help ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment of conditions that often go hand-in-hand with a systemic disease such as psoriasis.

With growing recognition that psoriasis is a “whole body” disease, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) collaborated for the first time to produce the joint AAD/NPF 2019 guidelines for managing plaque psoriasis, which included a section on comorbidities.1 The AAD last issued recommendations for managing related conditions in 2008 as a subtopic in guidelines for treating patients with biologic therapy. “But when the earlier guidelines were published, little was known about comorbidities of psoriasis,” says dermatologist Craig A. Elmets, MD, cochair for the new AAD/NPF guidelines and a professor of dermatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Now it’s quite clear that psoriasis is a systemic disease, and that skin disease is only one manifestation.”

Fortunately, the latest research summarized in the guidelines sheds light on which conditions are most common in patients with psoriasis. Here are the four major comorbidities of psoriasis—and expert recommendations for identifying and managing each one.

1. Psoriatic arthritis

Roughly one third of patients diagnosed with psoriasis eventually develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), typically about a decade after skin symptoms manifest. However, a minority of patients have joint symptoms (such as stiffness and swelling) at the time psoriasis is diagnosed. Psoriasis patients with a high degree of affected body surface area have the greatest risk for developing PsA.1

Untreated PsA can result in significant joint damage and diminished quality of life, making early detection critical, so the AAD/NPF guidelines recommend routine screening for PsA. “It can’t be something you do just at the first visit with a patient—screening for PsA has to happen on an ongoing basis,” says Dr. Elmets. Formal screening tools are available, though the AAD/NPF guidelines note that their reliability and validity are moderate. For that reason, Mark Lebwohl, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and a coauthor of the AAD/NPF guidelines, emphasizes the importance of careful assessment to identify PsA, including the following:

- Ask about joint pain, but be discriminate. “If the patient complains of a sore knee after playing tennis, and they have had that for 20 years, then I’m more likely to think that’s osteoarthritis,” says Dr. Lebwohl. On the other hand, if the patient has stiffness and swelling, especially in the fingers and toes, upon rising in the morning that resolves with activity, consider PsA as the cause.

- Look for asymmetry. Dr. Elmets notes that PsA often has asymmetrical presentation—for example, symptoms occurring in one knee but not the other.

- Check for lower back pain. This can be another red flag, says Dr. Elmets, since it may be brought on by sacroiliitis, which can occur in PsA.

- Be aware of other key signs, including enthesitis, or inflammation at the juncture where tendons and ligaments insert into bones. PsA patients often develop enthesitis in the Achilles tendon, though the hips, knees and other joints may be affected. Another problem: dactylitis, or inflammation of the small joints of the hands and feet, which produces “sausage-like” digits.

If you suspect PsA, consult the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/NPF guidelines for PsA and refer to a rheumatologist. “I take care of a lot of psoriatic arthritis patients but seek the help of a rheumatologist when I’m not sure of the diagnosis,” says Dr. Lebwohl, who notes that there are many drugs and drug combinations in the dermatologist’s armamentarium that can relieve symptoms of both psoriasis and PsA. A few things to consider: Methotrexate may reduce inflammation related to PsA but does not stop radiographic progression of the disease; other older agents are rarely adequate as monotherapy. Apremilast is approved for PsA but has not been shown to prevent the radiographic progression of joint disease. However, some biologics are also approved for PsA and prevent X-ray changes, including certain TNF inhibitors and IL-17 blockers. An IL-12/23 inhibitor is approved for PsA, although appears to be more effective for treating skin manifestations than joint symptoms. In addition, one IL-23 inhibitor is approved for PsA and others are under investigation. A TYK2 inhibitor is also being studied for PsA.2

2. Cardiovascular disease

People with psoriasis have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD); the more severe the psoriasis, the greater the threat. In a meta-analysis of nine studies, researchers assessed the CVD risk of 201,239 patients with mild psoriasis and 17,415 patients with severe psoriasis. Mild psoriasis conferred a 29% increased risk for myocardial infarction (MI), while severe disease increased the likelihood of developing CVD by 70%. Other research suggests that severe psoriasis increases the risk for stroke by up to 43%.1,3 One reason for the high incidence is the inflammatory nature of the disease. The American College of Cardiology has identified psoriasis and other chronic inflammatory diseases as risk factors for atherosclerosis. In addition, research suggests that people with psoriasis are more likely than those without the disease to have certain CVD risk factors. Notably, a study in JAMA Dermatology found a five-fold increased risk for coronary calcification in people with psoriasis.4 To help protect your patients:

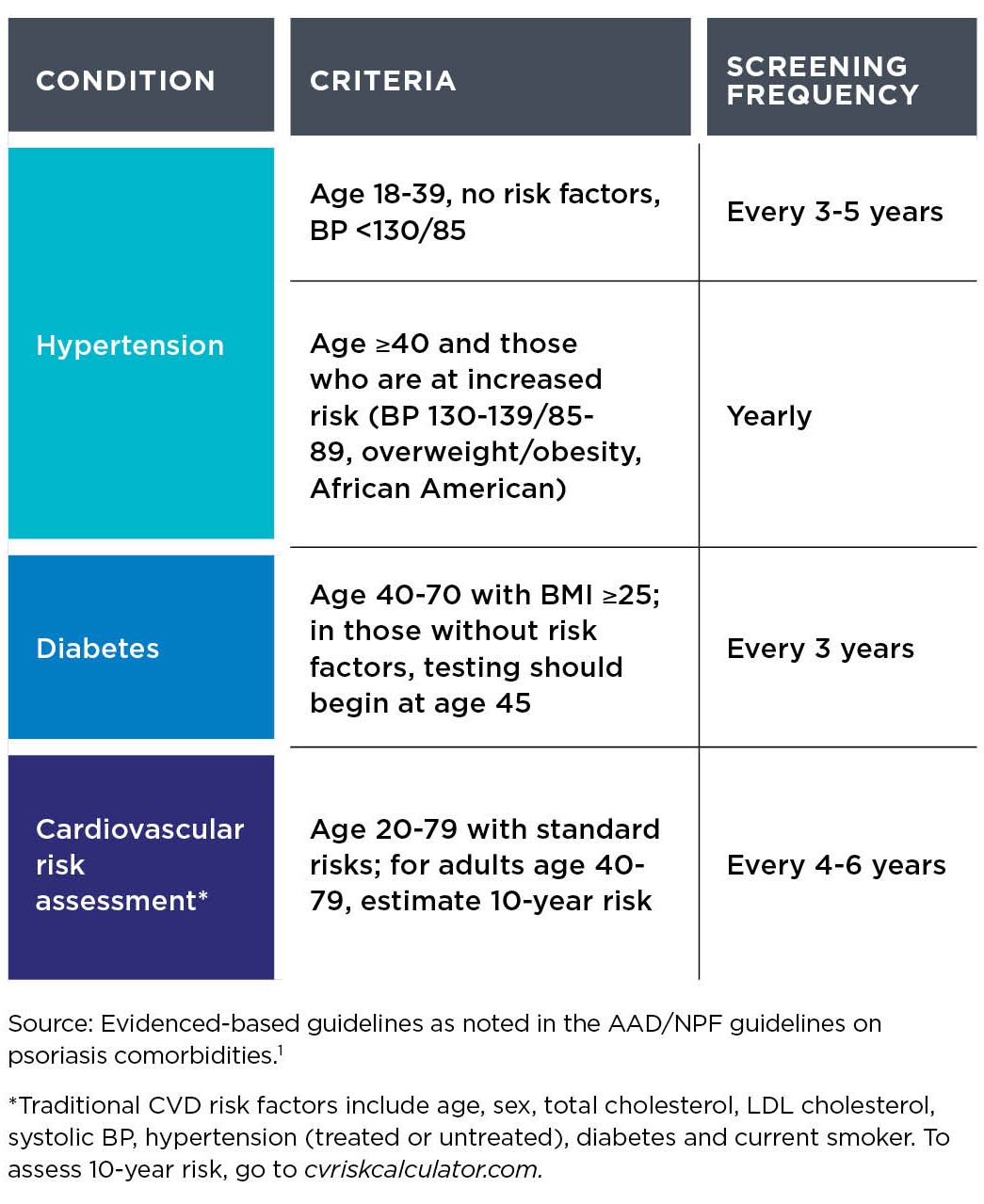

- Monitor risk factors. Blood tests performed for all psoriasis patients should include lipid panels, “so if a patient’s cholesterol is high, we direct him or her to see a clinician who can treat it,” says Dr. Lebwohl. Be sure patients have routine lipid screening, whether by you or another doctor (for recommendations, see Table 1, below).

- Consider the benefits of biologic therapy, especially in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and increased risk factors for CVD. Although clinical trials for biologics were not powered to detect cardiovascular benefits, later research suggests that the ability of these agents to suppress inflammatory pathways in the immune system may help lower CVD risks. For example, a study of 8,845 psoriasis patients found that those treated with TNF inhibitors had half the risk for MI compared with others given topical therapies. A follow-up study by the same group found that patients on a TNF inhibitor had a lower risk for major adverse cardiovascular events than others given methotrexate.1,5

Table 1.

Recommended CVD risk factor screening in patients with plaque psoriasis

3. Metabolic syndrome

People with psoriasis have an increased risk for developing the cluster of risk factors known as metabolic syndrome, which includes abdominal obesity, hypertension, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol and high fasting blood glucose. For a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, a patient must have at least three of the following:

- Increased waist circumference

(male, >40 inches; female, >35 inches) - Blood pressure >130/85 mmHg

- Fasting triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- Fasting HDL cholesterol levels <40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women

- Fasting glucose ≥100 mg/mL

One analysis found that roughly a third of psoriasis patients met the criteria for metabolic syndrome compared with about one quarter of controls, with the likelihood rising among patients with greater affected body surface area (≥10%).1 Metabolic syndrome increases the risk for CVD, type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, some cancers and premature death. It’s not clear why metabolic syndrome is more common among psoriasis patients, though a genetic link is being explored, says Dr. Lebwohl. Work closely with the patient’s primary care physician to control risk factors, and keep in mind the following:

- Be aware of psoriasis therapies that may contribute to CVD risk. For example, cyclosporine may cause or worsen hypertension, though the effects may be reversed by the calcium channel blocker amlodipine. Likewise, acitretin and cyclosporine can negatively affect lipids.

- Use a team approach to control hyperglycemia. Consider referring patients with prediabetes or newly diagnosed diabetes to an endocrinologist and/or certified diabetes educator, as these specialists can help patients get hyperglycemia under control quickly.

4. Obesity

Overall, people with psoriasis are 66% more likely than others to have obesity, which is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2, according to a review of 16 studies that included more than 2 million patients.6 The link between the two conditions is unclear, but studies suggest that losing weight can modestly improve management of the skin disorder. In a small trial, 60 patients with obesity and psoriasis (median Psoriasis Area Severity Index [PASI] score of 5) were randomly assigned to a low-calorie diet plan (800 to 1,000 calories/day for 2 months, followed by 1,200 calories/day for 2 months) or were simply instructed to eat healthy foods. Patients in the low-calorie group lost 34 pounds more than nondieters, on average, and reduced their PASI scores by an additional 2 points.7 “Reducing body weight makes psoriasis medications work better,” says Dr. Lebwohl, noting that it’s a matter of math: If two patients get the same dose of a drug, and one weighs 125 pounds and the other 250 pounds, the latter is getting half as much drug per unit of weight. To help patients maintain a healthy weight, try these strategies:

- Do a weight screening at least once a year. Calculate BMI and instruct patients who fall into the category of overweight (BMI 25 to 29.9) or obesity (BMI ≥30) to discuss weight-loss strategies with their primary care physician and/or refer them to an endocrinologist or other specialist in obesity medicine.

- Review their medications. Some therapies for various conditions are associated with weight gain, including antidepressants and beta blockers. In addition, studies suggest that two psoriasis medications, etanercept and infliximab, appear to promote modest weight gain, so keep in mind this potential downside when using these drugs.

- Consider bariatric surgery in select cases. For patients with a BMI ≥40 who fail conventional weight-loss strategies such as diet and behavior modification, strongly consider referral to a specialist in bariatric surgery. One study found that gastric bypass cut the risk for psoriasis progression from mild to severe by more than half. Note, though, that gastric banding (an alternative bariatric procedure) did not prevent worsening of skin manifestations.8

—Tim Gower

Other conditions associated with

plaque psoriasis

The AAD/NPF guidelines note that the following comorbidities are also important to be aware of. If you suspect any of the following, discuss it with your patient and refer to a specialist as necessary.1

Mental health issues

Psoriasis patients are roughly three times more likely than unaffected patients to experience anxiety and/or depression.1 Social withdrawal and sexual dysfunction are common, too, and associated with disease severity. However, studies strongly suggest that improvement of skin disease relieves psychological stress, with biologic therapy offering greater benefits than conventional systemic therapy or phototherapy.1

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Psoriasis patients have a four-fold increased risk for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, with psoriatic arthritis patients having the highest risk.9 While several TNF inhibitors are approved for treating IBD, these drugs can have the paradoxical effect of causing psoriasis-like eruptions, and discontinuing therapy doesn’t always resolve symptoms. One IL-12/23 inhibitor is also approved for psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. In addition, research suggests that IL-23 inhibitors may be beneficial for IBD. However, IL-17 blockade does not appear to help and can exacerbate IBD, although that is uncommon.

Cancer

Certain malignancies occur more often in psoriasis patients, including lymphomas; cancers of the head/neck and digestive tract; and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC). Be particularly mindful of NMSC in patients who have received psoralen ultraviolet light A photochemotherapy or cyclosporine. Several TNF inhibitors carry label warnings noting reports of lymphomas occurring in pediatric and adolescent users, and some studies have linked the drugs to an increased risk for NMSC. Malignancies have not been associated with IL-17 inhibitors or IL-23 inhibitors.

Renal disease

Psoriasis comorbidities such as hypertension and vascular disease can negatively affect the kidneys. However, psoriasis is also independently associated with renal disease, though why is unclear. In addition, chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which may be more common in patients with PsA, can impair kidney function. Also notable: Cyclosporine is contraindicated in patients with existing kidney disease, and renal disease impairs clearance of apremilast, so dose adjustment is necessary.

Uveitis

Patients with PsA have the highest risk for this condition caused by inflammation of the eye’s middle layer, which can cause permanent vision loss if untreated.10 Patients who develop redness of the eye (with or without pain), blurred vision or light sensitivity should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

More common in patients with metabolic syndrome and/or PsA, NAFLD is independently associated with psoriasis. Unidentified liver disease can result in not only fibrosis and cirrhosis, but also liver damage when certain psoriasis medications like methotrexate are prescribed for psoriasis. Early identification will help mitigate progression of liver disease and help ensure the best therapeutic options are used to manage the patient’s psoriasis.

Substance use

Though not comorbidities per se, smoking and increased alcohol consumption (more than 1 or 2 drinks a day) are associated with worsening psoriasis.

References

1. Elmets CA, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1073-1113.

2. Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: Which therapy for which patient: Psoriasis comorbidities and preferred systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):27-40.

3. Armstrong EJ, et al. Psoriasis and major adverse cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000062.

4. Mansouri B et al. Comparison of coronary artery calcium scores between patients with psoriasis and type 2 diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(11):1244-1253.

5. Wu JJ, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(11):1244-1250.

6. Armstrong AW, et al. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:e54.

7. Jensen P, et al. Effect of weight loss on the severity of psoriasis: a randomized clinical study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(7):795-801.

8. Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prognosis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(4):344-349.

9. Menter AM, et al. Common and not-so-common comorbidities of psoriasis. Seminars Cutaneous Med Surg. 2018;37(2S):S49-S52.

10. Egeberg A, et al. Association of psoriatic disease with uveitis: a Danish nationwide cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(11):1200-1205.

Overcoming

barriers to

treatment adherence

Building a partnership with your patients is the first step toward finding solutions to common challenges and, ultimately, improving outcomes.

Managing plaque psoriasis comes with unique challenges for both patients and healthcare professionals. Although there are more options than ever for controlling moderate-to-severe skin symptoms, research shows a range of factors can thwart treatment goals. For patients, a major impediment is lack of clarity about what the disease entails. “It’s the modern-day leprosy—there are so many myths and so much misinformation,” says Lakshi M. Aldredge, MSN, ANP-BC, a nurse practitioner in the Dermatology Service at the VA Portland Healthcare System in Oregon. “It’s a relatively common condition, but so much of the public and even some providers still don’t understand the disease and the implications for it.”

This lack of understanding can make it more difficult for patients to adhere to their treatment plan and adopt the lifestyle changes and coping strategies that can help improve their symptoms. What’s more, uncontrolled plaque psoriasis can increase the risk for many comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease and depression (see Strategies for managing comorbidities).1

The good news? A study coauthored by Aldredge in the Journal of the Dermatology Nurses Association found that relationship building—which includes identifying and breaking down roadblocks patients may be experiencing—is the key to success.2 “The more healthcare providers can help patients overcome these barriers, the better their treatment outcomes will be,” confirms Megan Rogge, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth in Houston. Here are some of the most common obstacles and how you can help patients overcome them—and in turn build a more effective partnership.

Patient barrier:

Inaccurate perception of the disease

“Really, truly understanding the whole picture of psoriasis can be overwhelming,” Aldredge says. “Many people believe it’s just a dry skin condition.” Dr. Rogge sees the same in her practice. “That belittles the disease burden and how much of an impact it can have,” she says. Sometimes, healthcare providers may unintentionally contribute to this view. “Some may say, ‘Here’s a cream. Use it and you’ll be fine,’ ” says Dr. Rogge. “The patient may feel like doctors don’t care about their skin and it’s a waste of time to see somebody”—which can worsen the disease.

How to overcome it: To correct this misperception, Dr. Rogge provides education about plaque psoriasis at the first visit, explaining that it’s a chronic autoimmune condition that raises their risk for other health problems. “It’s important for patients to realize that cardiovascular events, depression, joint problems and other conditions tend to occur more commonly in psoriasis patients,” Dr. Rogge says. “I talk about it to make sure patients are aware of these associations and will have proper follow-up.”

She also makes sure that patients know what the disease isn’t. “Some patients have a feeling that this is contagious or something that happened because they were dirty. They think they’re to blame,” notes Dr. Rogge. And if the psoriasis occurs in the groin or perianal region, patients may believe they have a sexually transmitted disease. “I provide counseling that this is nothing they did—it’s not a problem with hygiene and not something that’s contagious.”

“I tell my patients that having psoriasis may seem overwhelming, but over time it will get easier and their lives will get better.”

Patient barrier:

Lack of connection with their healthcare provider

Some patients may feel overwhelmed by what they learn about plaque psoriasis, which can result in their “checking out”—and not seeking further treatment for it, notes Aldredge.

How to overcome it: To prevent this, Aldredge stresses the importance of creating a strong therapeutic relationship. “You want to convince them that you’re there to help them for the long haul. You will help them in their journey through this disease,” she says. “I tell my patients that it may seem overwhelming, but over time it will get easier and their lives will get better.”

One technique she uses to get patients on board with treatment: Ask them, “What is your psoriasis keeping you from doing?” After they answer, she tells them that by next year at this time, they’ll be able to do what they wished for. “This gives them something to look forward to and the confidence that you’re taking care of them as a person, not just a disease, and that you’re invested in them.”

To reinforce what they’ve discussed, Aldredge also gives them literature to read at home at their own pace, refers them to the National Psoriasis Foundation’s website (psoriasis.org) for support and schedules a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks later. “I tell them to write down their questions and bring them to the appointment.”

Illustration by Michael Austin

Illustration by Michael Austin

Patient barrier: Unrealistic expectations

Dr. Rogge says that some patients may come to an appointment thinking there’s a quick fix for plaque psoriasis—and become impatient or even give up when the first medication they try doesn’t work.

How to overcome it: Dr. Rogge clearly explains that it will take time to find the right treatment and that some insurance plans do not make it easy. There are many different options to try, from creams and ointments to injectables or light therapy, and it may take a combination of treatments to keep the disease well-controlled. “To get approval for the newer drugs that don’t have as many side effects, insurance companies want you to try and fail everything else first,” notes Dr. Rogge. “I tell my patients, ‘Just be patient with us. It may take months to get approvals, but then it’s great because these medications work really well.’ I set those expectations early on that it’s not a prescription we can simply send to a neighborhood pharmacy right away.”

Patient barrier: Insurance coverage

Concerns about the expense of psoriasis drugs keep many patients from seeking treatment, Dr. Rogge says. Among the options for plaque psoriasis are biologics, which alter the immune system and are injected. “These newer biologic agents work incredibly well at getting patients almost completely clear of psoriasis, but you have to jump through hoops with insurance companies to get them covered,” says Aldredge. “It can be difficult for a patient to afford even the co-pay.”

How to overcome it: Aldredge says her office helps patients by connecting them with patient assistance programs set up by the pharmaceutical companies. “Every one of the newer biologic manufacturers has these programs,” she says. “It’s a free service that assesses the patient’s insurance status and gets them into the right channels to be able to get the drug.”

Another option is to contact the National Psoriasis Foundation, which connects patients to financial aid programs and can provide information and resources to help patients work with their providers to appeal insurance decisions.

Patient barrier: Depression

An extensive body of research, including a review of studies in Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, has shown a significant link between depression and plaque psoriasis.5 “In a patient with another autoimmune condition, such as type 1 diabetes, you can’t see the disease. But patients with psoriasis wear their disease on their skin for the world to see, which is very emotionally taxing,” Aldredge says. “They’re at higher risk for suicidal thoughts.”

How to overcome it: “From the second I walk in the room, I’m looking for signs that a patient may be depressed. Do they make eye contact? What is their mood? How are they dressed?” Aldredge says. On the other hand, many of her patients self-report depression. “They will say, ‘I’m miserable. I don’t want to be around people. I don’t want to participate in life,’” she says. She refers them to a mental health provider and may also prescribe an antidepressant. Therapy and medication can make a positive impact, as can improving psoriasis symptoms. “Once we get them clear, they’ll say, ‘I didn’t realize how emotionally drained I was,’ ” she notes. “If we get patients on the right treatment, it can really transform their lives. It’s so rewarding to see that.”

Patient barrier: Weight problems

“There is a correlation with obesity and the severity of psoriasis,” says Suzanne Friedler, MD, a clinical instructor in dermatology at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. “We don’t know which came first, but we know that patients with obesity are more likely to develop psoriasis.”

How to overcome it: Dr. Friedler refers her patients to their primary care physician for help with weight loss and advises getting outside for exercise. “Spending time outdoors can help with psoriasis and mood as well,” she says.

A review of clinical trials found that diet and exercise improve the overall health of psoriasis patients and have a positive impact on their Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores.3

Aldredge’s patients often ask her about eating plans and whether eliminating sugar or gluten will help with their disease. “I tell them there’s not a whole lot of literature that supports one diet over another, but the Mediterranean diet has been shown to help with any autoimmune or inflammatory disorder,” she says. A study in JAMA Dermatology backs that up, showing that eating a Mediterranean diet—which is high in anti-inflammatory foods like olive oil, vegetables, whole grains and fish and low in high-fat meat and dairy—may help reduce the severity of symptoms.4 The NPF also offers dietary recommendations at psoriasis.org. When it comes to getting more physical activity, says Aldredge, “I tell them that losing weight will help their psoriasis and that once we start clearing their skin, they’ll feel more comfortable walking or going to a gym.”

Patient barrier: Isolation

It’s very easy for psoriasis patients to become cut off from other people, even within their own families. But the disease affects the whole family, not just the patient, says Aldredge.

How to overcome it: Encourage patients to take a family member to each appointment. “It’s so important to get someone else as a partner in treating the disease,” Aldredge says. A loved one can also provide crucial information that the patient may withhold. “A patient may say his skin doesn’t bother him, but his wife will tell me he’s wearing long sleeves and pants even on the hottest days. Or he’ll say he doesn’t have joint pain, but she sees that he’s stiff when he wakes up,” notes Aldredge. “She may tell me that he never plays with the kids anymore because it’s too painful or he’s too embarrassed.”

All this information is important to understanding the full impact psoriasis has on the patient’s life and developing an effective treatment plan—which the family member can help the patient adhere to. “You want to get that second set of ears and also get their commitment and support,” notes Aldredge.

—Andrea Barbalich

References

1. de Oliveira M, et al. Psoriasis: Classical and emerging comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(1):9-20.

2. Aldredge L, et al. Providing guidance for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who are candidates for biologic therapy: Role of the nurse practitioner and physician assistant. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2016;8(1):14-26.

3. Alotaibi H. Effects of weight loss on psoriasis: A review of clinical trials. Cureus. 2018;10(10):e3491.

4. Phan C, et al. Association between Mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and severity of psoriasis. JAMA Dermatology. 2018;154(9):1017-1024.

5. Tohid H, et al. Major depression and psoriasis: A psychodermatological phenomenon. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;29(4):220-230.

Case Studies

PATIENT: SHAWN, 37, HAD A HISTORY OF UNCONTROLLED MODERATE-TO-SEVERE PLAQUE PSORIASIS BUT NO OTHER COMORBIDITIES.

“Shawn’s job was getting in the way

of his psoriasis treatment”

PHYSICIAN:

Melinda Gooderham, MD,

Medical Director of the SKiN

Centre for Dermatology,

in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada,

and vice president of the

Dermatology Association of Ontario

Treatment History:

Shawn, who worked at a nuclear power plant, had been on apremilast for a year before he came to see me. His initial body surface area (BSA) was 16%, and his static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score was 3. The apremilast had been working—it brought Shawn’s BSA down to around 4%—but it hadn’t completely controlled his psoriasis. He still had some scaly involvement on his lower legs, scalp and genital region. We tried adding a potent topical medication to resolve the remainder of the plaques on the body and a milder steroid for the genital region, but Shawn had trouble using the topical agents long enough to make a difference. That’s because his job required him to take a shower upon arriving at the site, and a second one before leaving for the day. Plus, the protective clothing Shawn needed to wear during his shift caused friction and triggered a lot of sweating, which made the topical medications smear and feel uncomfortable so they just weren’t being used.

Initiating treatment with a TYK2 inhibitor:

I asked Shawn whether he would be open to switching to a different oral medication called deucravacitinib, which, I explained, has been shown to be superior to apremilast, with fewer side effects. It could be taken without food, I added, and its once-daily dosing (versus twice a day for apremilast) would make it easier for Shawn to incorporate into his busy schedule. He agreed immediately. We stopped the apremilast and topical medications and started him on a course of deucravacitinib.

Within 4 months of taking the 6-mg starting dose of deucravacitinib, Shawn’s skin was completely clear, with a sPGA score of zero. No more greasy topicals or worries about missing a second daily dose! The latter was especially important to Shawn, as his shifts at the power plant were changing often, and management was asking him to work overtime on occasion. Because plaque psoriasis is a chronic condition, Shawn was thrilled to have found a medication that not only cleared his skin but also fit easily into his daily life.

Considerations:

Deucravacitinib is a first-in-class drug with a unique mechanism of action that selectively inhibits—or “turns down”—tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), thereby blocking several cytokines, including IL-12, IL-23 and type I interferon, that promote inflammation. Because deucravacitinib is so targeted, it doesn’t display a wide range of side effects; in clinical trials, nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection were the most common. Therefore, it doesn’t require the level of lab monitoring that may come with other systemic agents, which is definitely a relief to many of my patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

As a physician, it’s my job to treat patients effectively, while at the same time making it as easy as possible for them to adhere to their treatment regimen. In this regard, deucravacitinib checks both boxes. Busy patients like Shawn are happy, and I’m happy for them. For clinicians who treat chronic, often intractable conditions like plaque psoriasis, there’s truly no better outcome.

PATIENT: GARY, 54, HAD A 20-YEAR HISTORY OF MODERATE-TO-SEVERE PLAQUE PSORIASIS THAT HAD NEVER BEEN FULLY CONTROLLED. HE WAS ALSO BEING TREATED FOR HYPERTENSION.

“Gary’s injectable medications were not working out for him”

PHYSICIAN:

Melinda Gooderham, MD,

Medical director of the SKiN

Centre for Dermatology,

in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada,

and vice president of the

Dermatology Association of Ontario

Treatment history:

Gary, who was single and a smoker, collected disability insurance due to mental health issues that he had suffered from since his late teens. Unable to work, he lived with his wheelchair-bound mother in an urban area and served as her caretaker. Gary was diagnosed with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis roughly 20 years ago, for which he had taken topical medications, methotrexate and biologics, with only limited success. His condition had improved by roughly 50% since his initial diagnosis while taking his latest biologic.

Gary had a body surface area (BSA) of 22% and a static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 3 when he came to see me a year ago, and we switched him to a different biologic. Although he had avoided the drug’s more serious side effects, Gary consistently had injection-site reactions with each dose, mostly swelling and redness. His question to me was simply, “Don’t you have a pill I can take instead?”

Initiating treatment with a TYK2 inhibitor:

My answer to Gary was “Yes, we do!” I switched him off the topicals and the biologic and substituted once-daily deucravacitinib, a tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor. After 6 months on the drug, Gary’s BSA dropped to below 1% and his sPGA dropped to 1—both clinically significant improvements. And to my relief, he hadn’t reported any side effects with deucravacitinib and we had no concerns about interactions with his blood pressure meds.

Gary’s mood and self-esteem improved markedly. He felt better about himself, and his outlook toward his mother, whom he had considered a burden to him, brightened as well. As Gary left my office one afternoon, I couldn’t help but think that his life might have turned out differently had a medication with the efficacy and side-effect profile of deucravacitinib been available to him decades ago, when he was younger and more vulnerable to the often devastating psychosocial effects of a disease like plaque psoriasis.

“After 6 months on deucravacitinib, Gary’s BSA dropped to below 1% and his sPGA dropped to 1—both clinically significant improvements.”

Considerations:

In clinical trials, once-daily deucravacitinib demonstrated significant and clinically meaningful improvements in skin clearance, symptom burden and quality of life versus apremilast in adults with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. And, unlike apremilast, which requires twice-daily dosing, deucravacitinib is taken once a day. It may not sound like much of a difference, but I find that patients are far more adherent if they only have to remember to take a medication just once a day. Perhaps the biggest selling point when it comes to deucravacitinib is that it’s an oral medication we can offer to patients who are unable to take, or cannot tolerate, injectable biologics.

My patients who take deucravacitinib feel like they’re seeing real results, which goes a long way toward improving not only their psoriasis but the psychological effects of the condition. The embarrassment and discomfort they experienced for years are now largely a thing of the past, allowing them to focus on the important goals and personal relationships that bring meaning to their lives.

Q&A

Insight on managing plaque psoriasis

Encouraging healthy habits

Q: What type of lifestyle changes do you recommend for patients with psoriasis?

A: The number one thing is to stop smoking, which can impact the severity of disease and response to treatment. Because plaque psoriasis is linked with metabolic syndrome, I also talk about weight loss and encourage an annual physical to get lipids and cholesterol checked. A healthy diet that does not promote inflammation is also important. We want patients to eat good fats (e.g., monounsaturated fat such as olive oil), lots of vegetables and fish, and practice moderation with processed and sweetened foods. For some patients that leads to a gluten-free diet, but in my opinion there’s no clear evidence it’s effective for psoriasis. Therefore, I advise patients to maintain an overall healthy diet and lifestyle, including exercise.

It’s also important to talk about the job they do. For example, I had a patient who needed to lose weight, so I suggested he go for a morning jog before work—but it turns out he’s a nurse and works the night shift, so he sleeps during the day. Upon further probing, I found out he gets several breaks during his 12-hour shift, so I suggested that during those times he do short bouts of exercise, such as going up and down the stairs and taking the long way to the cafeteria. This experience reminded me I need to not just preach but focus more on a patient’s daily schedule and how to customize lifestyle recommendation to make them doable.

—Seemal R. Desai, MD, founder of Innovative Dermatology in Plano, TX; clinical assistant professor of dermatology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; and immediate past president of the Skin of Color Society

Taking a targeted approach

Q: What is the “treat to target” strategy for plaque psoriasis?

A: In a consensus statement published by the National Psoriasis Foundation, treatment targets are listed as guidelines for practitioners. An acceptable response is defined as a body surface area less than 3%, or 75% improvement from baseline within 3 months after starting treatment. The target response we’re aiming for is a body surface area less than 1% within 3 months after starting treatment. While these targets are ambitious, we now have medications that can indeed achieve these degrees of improvement, and it’s been shown that even small amounts of psoriasis negatively impact quality of life. However, certain patients may be satisfied with fewer degrees of improvement, and we have to take into account factors such as frequency of injections and monitoring requirements as well as cost.

Moreover, it’s not just body surface area that counts. In patients with certain comorbidities such as inflammatory bowel disease or concomitant infections, the impact of treatment is also important. The treat to target guidelines should be used as a tool to help dermatologists get the best medications possible for their patients with plaque psoriasis.

—Mark Lebwohl, MD, chair of the Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Medical Center

Homing in on scalp disease

Q: What is an everyday challenge for patients that may be underappreciated?

A: While patients can hide most plaques with clothing, they’re often self-conscious about visible scalp flaking, so it’s important to acknowledge this. I always ask, “Do you have flaking? Do you avoid wearing the color black?” Homing in on scalp symptoms opens the door to talking about hair care practices, which is particularly important in African American patients. Some only wash their hair once a week, so I talk about styling and grooming practices. I suggest that for the next month or two, try washing two to three times a week. Then when the flaking is under control, they can go back to once a week. I also tell patients to avoid gels and pomades, which can leave a layer that prevents absorption when medicine is applied to the scalp. For physicians, I recommend consulting resources at the Skin of Color Society (skinofcolorupdate.com), which offers multicultural dermatology education for diverse populations.

—Seemal R. Desai, MD

Ways to control itching

Q: How do you help patients manage psoriatic itch?

A: We have to remind dermatologists to talk about itching. We are programmed to talk about itch with eczema, and I have to remind myself that plaque psoriasis is also very, very itchy. I get sidetracked on other issues and forget to ask, “How itchy are you?” To treat psoriatic itch, I use oral antihistamines. I also like phototherapy. We are now recognizing the itch part better, and it can be as simple as antihistamines, UV light treatments and emollients, which are very good at relieving the itch. Of course, medications that treat psoriasis will also help, and some newer agents have good data on controlling itch.

— Seemal R. Desai, MD

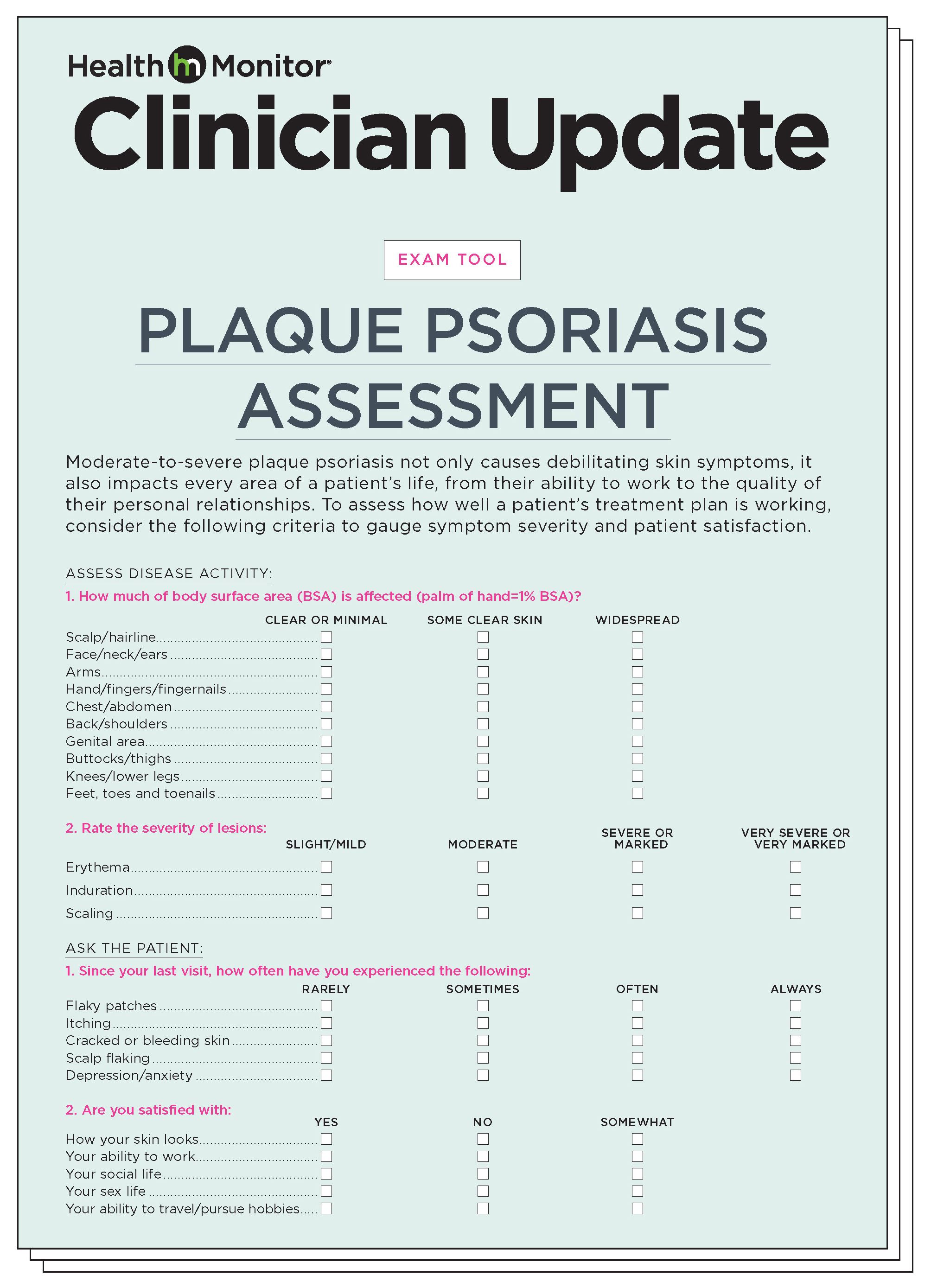

Plaque psoriasis assessment

Moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis not only causes debilitating skin symptoms, it also impacts every area of a patient’s life, from their ability to work to the quality of their personal relationships. To assess how well a patient’s treatment plan is working, consider the following criteria to gauge symptom severity and patient satisfaction.

Click here to download a printable version of the assessment tool.

Clinical minute:

Test your knowledge of plaque psoriasis treatment

Special thanks to our medical reviewers:

Tina Bhutani, MD

Co-director, UCSF Psoriasis and Skin Treatment Center, San Francisco

Mark G. Lebwohl, MD

Professor and Chairman, Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

And thanks to the National Psoriasis Foundation for their review of this publication.

Maria Lissandrello, Senior Vice President, Editor-In-Chief; Lori Murray, Associate Vice President, Executive Editor; Lindsay Bosslett, Associate Vice President, Managing Editor; Joana Mangune, Senior Editor; Marissa Purdy, Associate Editor; Erica Kerber, Vice President, Creative Director; Jennifer Webber, Associate Vice President, Associate Creative Director; Ashley Pinck, Associate Art Director; Molly Cristofoletti, Graphic Designer; Kimberly H. Vivas, Vice President, Production and Project Management; Jennie Macko, Senior Production and Project Manager; Taylor Wexler, Director, Alliances & Partnerships

Dawn Vezirian, Vice President, Financial Planning and Analysis; Donna Arduini, Financial Controller; Tricia Tuozzo, Sales Account Manager; Augie Caruso, Executive Vice President, Sales & Key Accounts; Keith Sedlak, Executive Vice President, Chief Growth Officer; Howard Halligan, President, Chief Operating Officer; David M. Paragamian, Chief Executive Officer

Health Monitor Network is the leading clinical and patient education publisher in dermatology and PCP offices, providing specialty patient guides, discussion tools and digital wallboards.

Health Monitor Network, 11 Philips Parkway, Montvale, NJ 07645; 201-391-1911; customerservice@healthmonitor.com.

©2022 Data Centrum Communications, Inc.

TCO22