Insight on using a new oral TYK2 inhibitor

In September 2022, the oral medication deucravacitinib became the first TYK2 inhibitor approved for plaque psoriasis—and follow-up data from an ongoing extension trial confirmed the agent’s durable efficacy for up to 2 years of continuous treatment.1 This is welcome news for the roughly one-third of patients who reported dissatisfaction with their current therapy in a survey by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF).2

“Dermatologists now have another treatment option that can help patients overcome their plaque psoriasis long-term,” says Mark Lebwohl, MD, Professor and Chairman Emeritus of the Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, and Dean for Clinical Therapeutics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “Deucravacitinib has been shown to be safe and well tolerated, so it should become widely used in practice.”

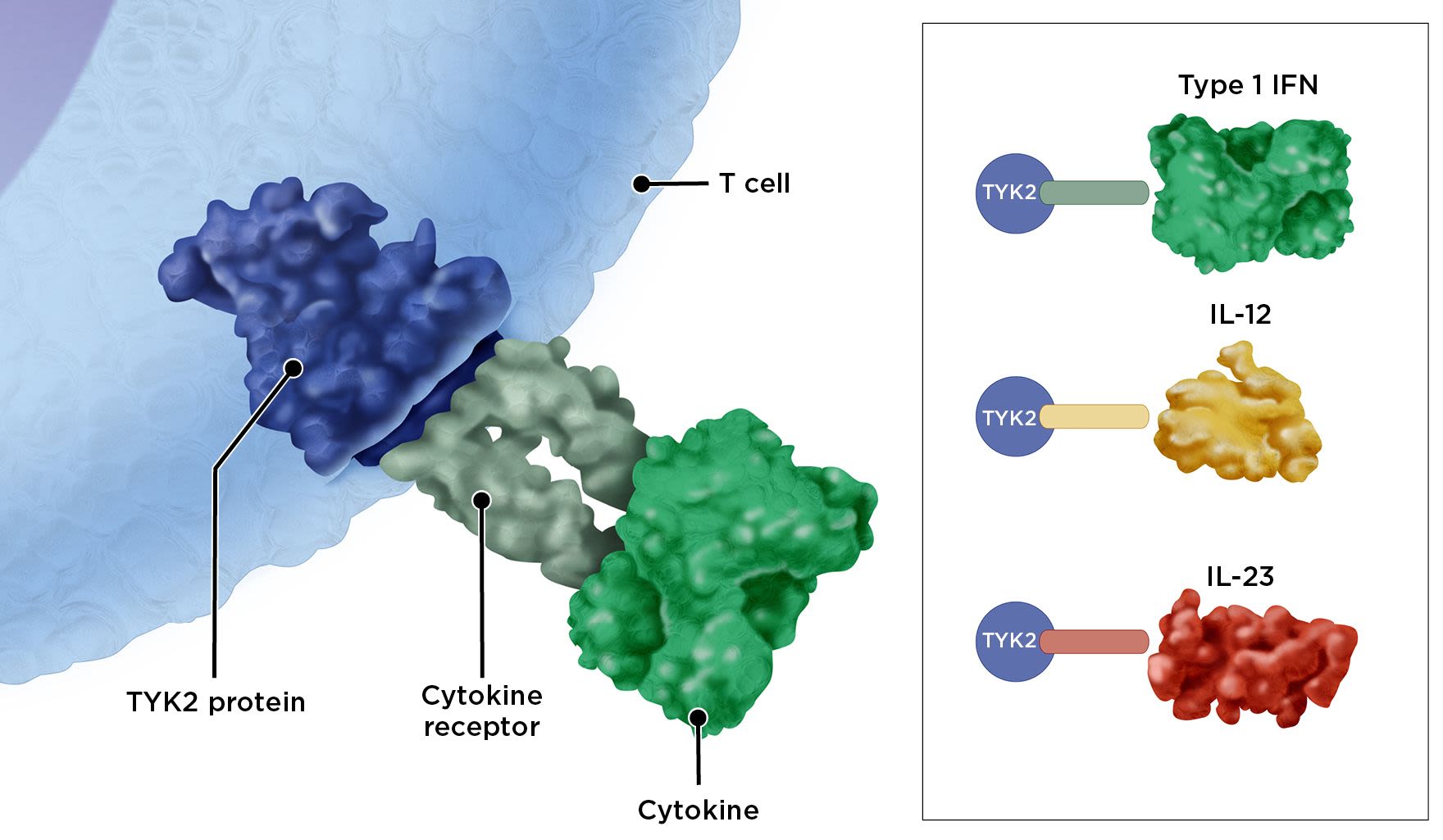

Figure 1. Deucravacitinib: First-in-class TYK2 inhibitor with a novel mechanism of action

Targets TYK2, thereby inhibiting key

inflammatory cytokines

Illustration by Suzanne Ghuzzi Silva

Illustration by Suzanne Ghuzzi Silva

Follow-up data reinforces previous trials

The clinical trials that led to FDA approval, POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2, showed patients responded significantly better to deucravacitinib than apremilast and placebo.3 The data showed that twice as many deucravacitinib-treated patients saw improved Static Physician's Global Assessment (sPGA) scores and at least a 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores over 1 year vs. those receiving apremilast, and five times as many patients improving on deucravacitinib vs. those on placebo.4

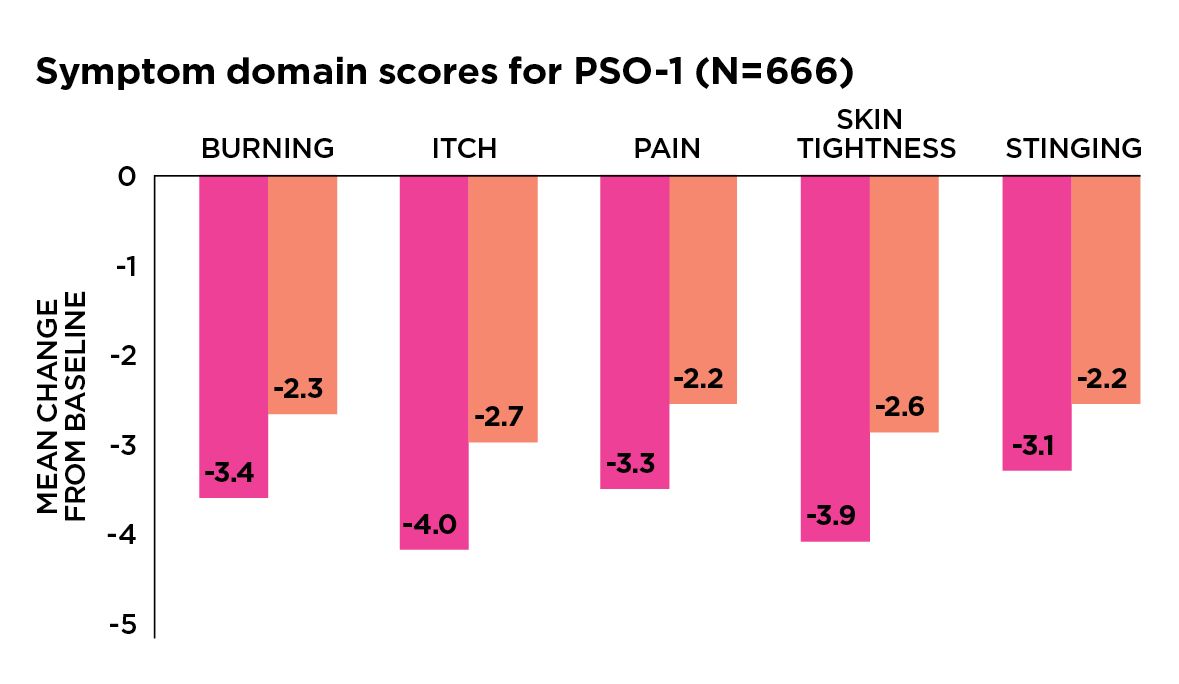

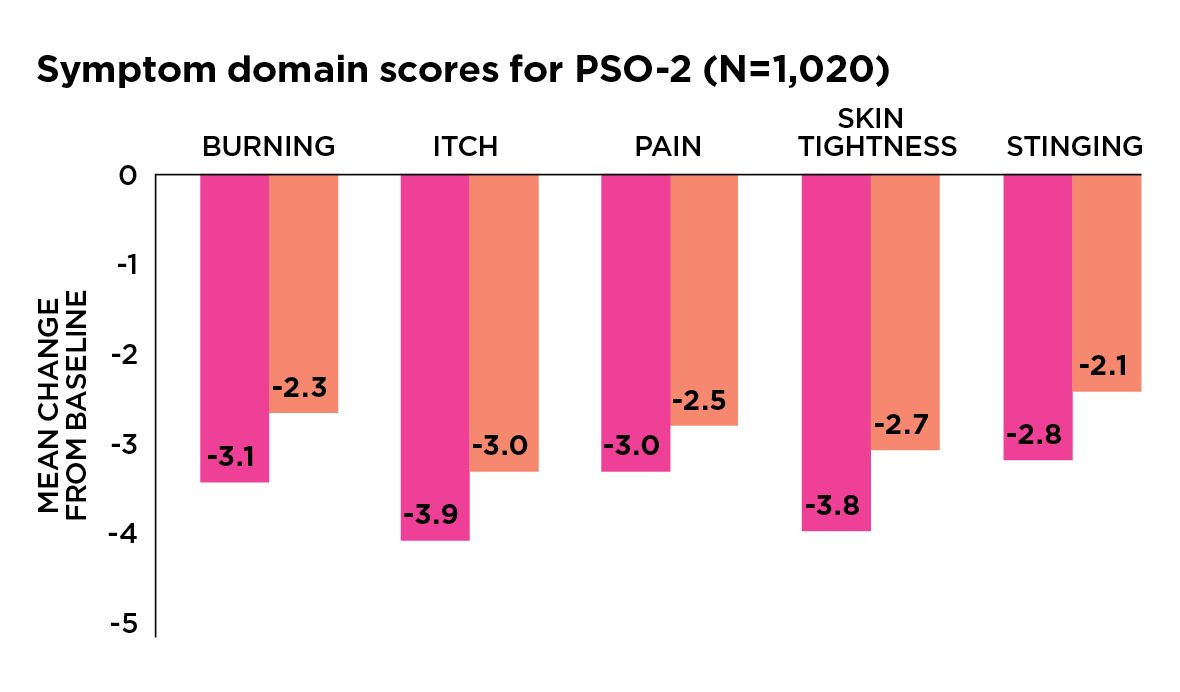

Figure 2. Deucravacitinib vs. apremilast: Mean change in psoriasis symptom scores in the POETYK PSO trials at Week 24*8

*P<0.01 vs. apremilast. Scores based on patient-reported assessments for the Psoriasis Symptoms and Signs Diary.

Soon after FDA approval, results from the long-term extension trial were presented at the 2022 meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Response rates for PASI and sPGA 0/1 (clear/almost clear) scores at the 1- and 2-year marks, respectively, were:1,5

- PASI 75: 90.1% (week 52) and 91.0% (week 112)

- PASI 90: 64.9% (week 52) and 63.0% (week 112)

- sPGA: 73.7% (week 52) and 73.5% (week 112)

The main takeaway: After 2 years, patients showed no loss of benefit from deucravacitinib treatment and no safety issues (see below). These results suggest that “deucravacitinib has the potential to become a major new oral therapy for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis,” says Dr. Lebwohl.

Favorable safety profile fills treatment gap

Another reassuring outcome: The follow-up trial found no red flags related to safety. This is a key finding, as many oral and injectable systemic therapies carry an increased risk of adverse events, including serious effects on immune function and major organ systems. “Because of these adverse effects, dermatologists and patients alike have identified the need for more effective and tolerable oral therapies,” says Dr. Lebwohl.

Fortunately, 2-year data for deucravacitinib showed low rates of major adverse events, including serious infections, major adverse cardiovascular events, malignancies, venous thromboembolism and herpes zoster. “The drug appears to be very safe,” Dr. Lebwohl says. The most common side effects include upper respiratory infections, acne and oral ulcers.

In contrast, other systemic therapies, while effective, often come with downsides. For example, methotrexate can cause GI distress, liver toxicity and bone marrow suppression, while cyclosporine can cause hypertension and kidney damage and can predispose to malignancy, Dr. Lebwohl says. Acitretin, an oral retinoid, can cause distressing local side effects such as skin rashes and hair loss, and it causes birth defects. Apremilast, an oral PDE4 inhibitor, has a benign side-effect profile but has shown only modest real-world benefit against plaque psoriasis, notes Dr. Lebwohl. With biologics, certain ones can increase the risk of infections and malignancy. And because these agents are injected or infused, Dr. Lebwohl says, they can cause injection-site pain and allergic reactions.

TYK2 inhibition: What makes it different

Deucravacitinib, a once-daily oral agent, works by targeting tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), an enzyme in the Janus kinase family that also includes JAK1, JAK2 and JAK3. Of the entire JAK family, TYK2 is mainly involved in chronic inflammation.6 As a TYK2 inhibitor, deucravacitinib blocks inflammatory cytokine signals without affecting JAK pathways that have more broad systemic effects. In contrast, JAK inhibitors block cytokine signals but also work on nontargeted pathways, which may increase the risk of malignancy, cardiovascular events, blood clots and other adverse effects.6,7 The unique mechanism of action of deucravacitinib gives it not only a high degree of efficacy but also safety, as shown in clinical trials, with no monitoring requirements.1,3,4

Strategies for using deucravacitinib

Dr. Lebwohl recommends the oral agent as a first- or early-line medication for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. “There are many circumstances where a pill might be preferred over an injectable,” he says. In general, deucravacitinib may be a good option for a patient who:

- Is not responding to current systemic therapy.

- Is injection averse or simply prefers oral medication.

- Has moderate psoriasis that doesn’t call for a biologic but requires systemic therapy.

- Cannot follow an injection schedule due to life circumstances. For example, an injectable might be burdensome to a frequent traveler, or to a college student who doesn’t have refrigerator space to store biologics or has trouble finding a private place to inject.

- Has symptoms that include:

Palmoplantar plaque psoriasis. Deucravacitinib comprises a small molecule that can travel seamlessly through small blood vessels to peripheral areas of the body, notes Dr. Lebwohl. “Treating palmoplantar plaque psoriasis with a biologic that is a larger molecule can be challenging,” he says.

Itching. Deucravacitinib showed significantly superior efficacy for relieving itching vs. apremilast (see Figure 2, above).8

Another advantage: Deucravacitinib is a pill taken just once a day (6 mg), with or without food. It does not need dose titration. However, set expectations by telling patients they might not see the full benefits for as long as 4 months.

What to know before prescribing

As for any psoriasis therapy that suppresses part of the immune system, avoid using deucravacitinib in patients with an active infection or malignancy, Dr. Lebwohl says. Also, vaccinations might necessitate brief pauses in treatment, although the data aren’t clear on this issue and it might depend on the type of vaccine.

If coverage is an issue, consider requesting drug samples from the manufacturer and offer them to patients who cannot access the drug quickly, suggests Dr. Lebwohl. The manufacturer also has a copay assistance program that can help offset cost. In addition, the NPF can connect patients to financial aid programs and provide resources to help them work with their providers to appeal insurance decisions (visit psoriasis.org).

—Pete Kelly

References

1. Lebwohl M. Deucravacitinib long-term efficacy with continuous treatment in plaque psoriasis: 2-year results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO study program. Abstract #D3T01.1F. Presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress, September 10, 2022.

2. Lebwohl MG, et al. US Perspectives in the Management of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: Patient and Physician Results from the Population-Based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) Survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:87-97.

3. Warren R, et al. Deucravacitinib, an oral, selective tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: 52-week efficacy results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 trials. Poster presentation. SKIN. 2022;6(2).

4. Armstrong AW, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial [published online ahead of print]. J Am Acad Dermatol. July 8, 2022.

5. Bristol Myers Squibb announces new deucravacitinib long-term data showing clinical efficacy maintained for up to two years with continuous treatment in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (press release). Published September 10, 2022.

6. Kvist-Hansen A, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with JAK inhibitors: A review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):29-42.

7. Snow M, et al. Janus kinase inhibitor boxed warning. Statement from the American College of Rheumatology. Updated January 28, 2022.

8. Armstrong AW, et al. Deucravacitinib improves psoriasis symptoms and signs diary domain scores in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 and POETYK PSO-2 studies. Poster presented at the Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference, October 2021, Las Vegas.

OPTIMIZING

CARE IN PATIENTS

WITH SKIN

OF COLOR

Psoriasis impacts people of all skin colors, but in recent years, evidence has come to light that suggests psoriasis is undertreated in those with darker skin tones, particularly Black persons. In the United States, it’s estimated that about 1.9% of Black, 1.6% of Hispanic and 1% of Asian patients have psoriasis versus 3.6% of White Americans; however, some experts question if those numbers are underreported.1 In addition, research indicates Black patients may have more severe symptoms and flare-ups overall compared with White patients.2

Despite this, research suggests people with skin of color who have psoriasis report fewer office visits for disease management,3 while those seeking to find out what’s causing their skin issues face another barrier: Dermatologists are less confident about diagnosing psoriasis in people with darker skin tones than those with lighter ones.2 Two reasons that may account for this: 1) Plaques can show up differently on darker skin, such as brown, purplish or gray discoloration versus the pink and red plaques typically found on lighter skin; and 2) The imagery of many skin conditions, including psoriasis, in medical resources have featured White patients.

What’s more, Black, Asian and Hispanic patients with psoriasis report a greater impact on their quality of life compared with White patients, regardless of disease severity.4,5 While there could be several contributing factors, Junko Takeshita, MD, PhD, MSCE, an Assistant Professor of Dermatology and Epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania who heads a research program dedicated to eliminating healthcare disparities in dermatologic diseases, hypothesizes that at least part of the reason is the increased hyperpigmentation these patients experience after their plaques heal. “So even when the active disease is gone, people with darker skin are more likely to experience discolored skin—sometimes that lasts for months,” she says.

While the American Academy of Dermatology has a task force developing an official skin color curriculum, there are immediate steps you can take to improve care in undertreated populations. Here, Dr. Takeshita and other experts discuss typical challenges and how to overcome them.

Challenge: Hyperpigmentation

How to overcome it: Focus on prevention.

Corey L. Hartman, MD, FAAD, Assistant Clinical Professor of Dermatology at the University of Alabama and founder and medical director of Skin Wellness Dermatology in Birmingham, says he sees many patients come in for help with the hyperpigmentation left behind after plaques have cleared. However, this discoloration is difficult to manage. His strategy: Change the focus to prevention. He starts by telling patients that while he can treat the hyperpigmentation, the available options can be expensive and uncomfortable—and are ultimately not as effective as preventing plaques in the first place. So the goal, he explains, is to avoid hyperpigmentation before it starts by treating their psoriasis rather than the aftereffects.

Challenge: Not receiving the right therapy

How to overcome it: Explain all their options.

There are certain systemic disparities that can hinder treatment in Black patients. For example, in a study by Dr. Takeshita that analyzed Medicare recipients, Black patients with psoriasis were 69% less likely to receive biologics than White patients—regardless of socioeconomic and other demographic factors.6 And, she says, “Among Black individuals who had never received biologic therapy, a common theme was that they were unfamiliar with the medication. This was not the case among White individuals. To me, this means that Black patients with psoriasis have less exposure to and/or are less likely to recognize biologics as therapeutic options for them.”

One problem may be lack of marketing. When Dr. Takeshita and her research team studied prime time TV commercials for psoriasis and eczema treatments on four major channels over a 2-week period, they found that about 93% of the main “characters” were portrayed by White actors while only 6% featured Black actors.7 This can impact both the likelihood of Black patients being offered a medication, as well as their understanding of whether it could be a good treatment for them. Therefore, it’s crucial to make sure patients with skin of color understand all their options and feel empowered to choose one. It’s also important to be alert to potential barriers. Dr. Takeshita says that when she runs into resistance to treatment, she leans in with curiosity. “I always ask, ‘Do you mind me asking, what are you most concerned about?’ ” Knowing the answer allows her to address the issue or suggest another treatment.

Challenge: Different needs for scalp care

How to overcome it: Offer practical solutions.

Dr. Takeshita advises being aware of cultural sensitivities when treating scalp psoriasis in people with curly or dryer hair, which includes many Black patients. “Typically, these individuals are not washing their hair daily,” she points out, and some may wash their hair just once a week, so a daily medicated shampoo may not be the best option for them. “You’ve got to ask what your patient is doing and align your recommendations with their habits and their values,” she notes. For example, try asking, “Do you have flaking? Do you avoid wearing dark-colored clothing?” Homing in on scalp symptoms opens the door to talking about hair care practices and treatments that work with their daily routine—for example, is it easier for them to use a topical and what vehicle do they prefer (e.g., solution, lotion, foam, etc.).

Challenge: The stress of living with psoriasis

How to overcome it: Discuss self-care strategies.

Naana Boakye, MD, MPH, of Bergen Dermatology in Englewood Cliffs, NJ, says one topic she doesn’t think gets talked about enough is stress reduction. Her advice is to address it from two angles: “I encourage patients to do some form of movement and some form of mindfulness.” For movement, she keeps it simple. “Exercise does not mean that you have to be at a gym—I tell my patients that all the time, and instead suggest they go for a brisk walk,” she explains. When it comes to mindfulness, she recommends yoga, breathwork or free meditation apps such as the Smiling Mind or UCLA Mindful app.

Seeking support from family can also be a good way to alleviate the feelings of isolation and stress that come with psoriasis—and it can have an added benefit for Black patients in spreading awareness to family members who may also have a genetic risk for the condition. Dr. Hartman calls lack of awareness in the Black community “multifaceted, but it kind of goes back to the same problem of underrepresentation.”

Challenge: Lack of access to healthy food

How to overcome it: Suggest alternatives.

Dr. Boakye points out that psoriasis comes with a risk of cardiovascular disease. “This is a big concern in the Black population. Lifestyle is very important.” While there isn’t a specific diet recommended for improving psoriasis, a healthy eating plan that does not promote inflammation and lowers cardiovascular risk is essential. But the standard advice to eat fresh, unprocessed food from the produce aisle can be a hurdle due to cost as well as “food deserts”—neighborhoods that are far from grocery stores offering fresh food, which are more commonly found in Black and brown communities.8 Dr. Boakye says one solution is to buy frozen fruits and vegetables, which is not only more economical, but they also last longer, making it easier to stock up when they’re on sale. She advises her patients to eat whatever frozen vegetables they like and to pair with brown rice or quinoa for an economical meal that’s low in sodium and sugar. However, if canned options are more readily available, advise patients to choose low-sodium versions, avoid fruit canned with syrup and rinse off salty or sugary liquids.

—Beth Shapouri

How to identify psoriasis in skin of color

Seemal R. Desai, MD, FAAD, founder of Innovative Dermatology in Plano, TX, and past president of the Skin of Color Society, acknowledges a major reason for underdiagnosis: “There is a lack of public awareness that there are dermatologic diseases in skin of color. We need to do a better job educating the public,” he says. Another problem: “A lot of times patients don’t get to see a dermatologist because they don’t have insurance or their condition is treated as dry skin, for example, by their primary care physician, who doesn’t realize this is psoriasis.” When a person of color does present in your office, Dr. Desai suggests the following strategies to help make a diagnosis:

Consider cultural sensitivities when conducting an exam. “Certain cultures don’t want to show their skin at all. Some don’t want to get into a robe or gown. Some patients want a more holistic care approach. But psoriasis in skin of color is not uncommon; we need to make sure we are screening these patients. I recommend a full-body skin exam, looking from head to toe. That’s very important—just because we don’t see psoriasis on the elbows doesn’t mean we won’t see it on the genitals. We also have to be sure to ask the right questions, such as ‘What part of your body bothers you the most?’ Some may not want to get certain parts looked at or treated, so we need to ask.”

Look for telltale signs. “The lesions are often less scaly, and physicians may not notice the ‘silvery scale’ you classically expect with psoriasis. Also, the redness may not be as visible on a darker skin tone. It may look more like hyperpigmentation than inflammation.”

Learn about best practices. “I recommend consulting resources at the Skin of Color Society (skinofcolorupdate.com), which offers multicultural dermatology education for diverse populations. It’s not just about understanding diagnosis, it's also about management. The treatment options that we would use in a patient with a lighter skin type may not always be ideal for a patient with a darker skin tone. For example, phototherapy is not something we use in our patients with a darker skin type without having the discussion that it can potentially cause their skin to become darker in other areas of the body. Topical steroids can also affect the skin tone. In addition, there are dermatologists who specialize in skin of color whom you can consult or refer to; some patients may prefer being treated by a specialist who is well versed in the types of challenges particular to their race/ethnicity.”

References

1. Rachakonda TD, et al. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512-516.

2. Alexis AF, et al. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(11):16-24.

3. Fischer AH, et al. Health care utilization for psoriasis in the United States differs by race: an analysis of the 2001-2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78(1):200-203.

4. Takeshita J, et al. Racial differences in perceptions of psoriasis therapies: implications for racial disparities in psoriasis treatment. J Investigative Dermatol. 2019;139(8):1672-1679.

5. Shah SK, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(8):866-872.

6. Takeshita J, et al. Psoriasis in the US Medicare population: prevalence, treatment, and factors associated with biologic use. J Investigative Dermatol. 2015;135(12):2955-2963.

7. Holmes A, et al. Content analysis of psoriasis and eczema direct-to-consumer advertisements. Cutis. 2020;106(3):147-150.

8. Bower KM, et al. The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States. Prevent Med. 2014;58:33-39.

Implementing

weight-loss

therapy to

improve outcomes

Psoriasis has been closely linked with overweight and obesity. One review of the literature noted several studies, including the renowned Nurses’ Health Study, that made this connection.1 One such study found that the risk for psoriasis development in those with obesity was twice that of those with normal body weight. In addition, for each unit increment increase in body mass index (BMI), there was a 9% higher risk for psoriasis onset and a 7% higher risk for increased Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) score. Another found that the three common measures of excess weight—BMI, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio—all correlated to PASI-measured severity, suggesting that excess adiposity may be a risk factor for disease severity.

Because overweight and obesity also correlate with metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, both of these conditions are frequently comorbid with psoriasis.2 “There is a very strong demonstration of the relationship, and I observe it very frequently clinically, as well,” says Sonya Kenkare, MD, FAAD, Assistant Professor of Dermatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

Why this is so, however, “is not clearly understood,” she says. “They all are associated with some level of baseline inflammation.” Indeed, patients with psoriasis have an increased incidence of diabetes even when controlling for BMI and other risk factors, such as smoking, cardiovascular disease and hypertension.2 In addition, says Dr. Kenkare, “Metabolic syndrome is not always because of being overweight—for instance, some patients have advanced age or strong genetic predisposition.”

It is well established that weight loss helps control inflammation and is a major component of diabetes control. But “there is also a direct correlation with improved psoriasis and weight loss,” Dr. Kenkare says. One study of psoriasis patients with a BMI >27 found that the group on a very-low-calorie diet lost significantly more weight than those on a routine diet, and this group reported a greater reduction in PASI and greater improvement in the Dermatology Life Quality Index than the control group.1

One explanation for this seems to be a connection between weight and medication efficacy, particularly with biologics, as obesity has been associated with both increased severity of psoriasis and poor treatment response.3 “Those with weight in the normal range do better with standard doses of medications. At the higher BMI range, standard FDA-approved dosages of biologics may be less effective,” she notes.

For all these reasons, losing excess weight is often recommended to help control psoriasis in patients with a high BMI. Here, Dr. Kenkare offers some tips she gives her patients to help them achieve their weight-loss goals.

Address the topic openly.

Psoriasis and comorbid overweight/obesity are not to be taken lightly. “Patients with psoriatic arthritis need to be especially careful, because it can cause irreversible damage,” Dr. Kenkare says. Her patients know that chronic psoriasis results in a lower quality of life, and “though I am not a dietitian, my patients and I talk about weight all the time.”

Encourage healthy eating.

Dr. Kenkare gives patients simple ways to adopt a healthy eating plan:

- Increase the amount of vegetables in the diet. “Look at your plate; make it half veggies, at least one-quarter protein and the rest carbohydrates,” she says. “That helps get you a lower overall calorie content, with more nutritional density and fiber.”

- When snacking, “reach for fruits and veggies, not processed food,” she says. Not only are these snacks healthier, their high-fiber, nutrient-dense calories “are also more satisfying.”

- Drink plenty of water, which helps you feel full, and avoid soft drinks and other high-calorie beverages.

- Avoid alcohol, which contains “empty” calories. Alcohol consumption can also be associated with worse psoriasis.

Suggest simple exercise habits.

There is no need to join a gym. “Asking someone who is sedentary to run is like a punishment. Just walking is helpful,” Dr. Kenkare stresses. She tells her patients to try to walk 30 minutes a day, three to four times a week, in the beginning. If that’s too much, start lower. “Walk around the block. Then as you build stamina, keep increasing the distance.” Aim for 30 minutes. When that’s comfortable, then increase gradually up to an hour, and try to do that five times a week. “There is value beyond calories burned,” she adds. Exercise offers stress relief and lowers cortisol, which is also linked to weight gain. “Stress release adds a lot of value.”

Advise a consultation with a PCP or endocrinologist.

As Dr. Kenkare notes, dermatologists are not necessarily experts in nutrition, exercise and weight loss. A PCP addresses these topics more often and can connect patients with resources and other experts, such as an endocrinologist, dietitian and physical therapist.

In the case of someone with a BMI over 35, bariatric surgery may be an option. Studies are mixed as to whether bariatric surgery does indeed help reduce symptoms and prevent onset of psoriasis.4,5,6 But anecdotally, “so many improve” after surgery, Dr. Kenkare says. “It improves quality of life and their ability to manage their condition and other comorbidities.” For example, one of Dr. Kenkare’s patients with a BMI of 40 had gastric bypass surgery; with her weight in the normal range, she was able to reduce her psoriasis medications by half and had less need for topicals.

Take advantage of technology.

Apps like MyFitnessPal and Apple’s Health are very helpful, Dr. Kenkare says. “Though it’s not true for everyone—there are some medical and genetic reasons for being overweight—in a general sense, weight is based on calories consumed related to calories burned,” she says. By logging what you eat and how far you walk into a fitness app, “you get a numeric idea of what’s happening. If you are diligent about recording what you eat and what you do, you’re getting a mathematical, quantitative amount of data as to what’s going in, what’s going out and what you are netting.” In addition, says Dr. Kenkare, “The internet is full of high-fiber, high-protein and low-carb recipes, and those are the types of macronutrients that can be helpful for feeling full while eating nutritionally dense foods with reasonable calories,” says Dr. Kenkare. For example, Eatingwell.com, she says, has a special section of diabetes-friendly recipes.

Focus on health, not just weight.

“I would like to stress that, even with normal weight, some people with psoriasis also have problems like diabetes or high cholesterol. Getting those in control can also improve psoriasis,” Dr. Kenkare says. She notes a patient who had a normal BMI of 22 but bloodwork revealed an A1C of 12%, and her psoriasis was unmanageable. “She was shocked she had diabetes,” Dr. Kenkare says. Once she got her blood sugar under control, her psoriasis improved. While this woman was in her 70s, Dr. Kenkare reports that normal weight is also “pretty common in people with a general history of high cholesterol, even in young people in their 30s and 40s.”

—David Levine

References

1. Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis: Part I. Impact of weight loss interventions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):133-140.

2. Yan D, et al. New frontiers in psoriatic disease research, Part II: Comorbidities and targeted therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141(10): 2328-2337.

3. Wu M-Y, et al. Change in body weight and body mass index in psoriasis patients receiving biologics: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 82(1): 101-109.

4. Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prognosis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(4):344-349.

5. Yako E, et al. Bariatric surgery and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(4):774-779.

6. Hossler E, et al. Gastric bypass surgery improves psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 65(1):198-200.

Case study

PATIENT: TAYLOR, 19, IS A COLLEGE STUDENT WITH A 3-YEAR HISTORY OF MODERATE-TO-SEVERE PLAQUE PSORIASIS

“Taylor’s psoriasis was thwarting her college goals”

PHYSICIAN:

Bruce Strober, MD, PhD,

Clinical Professor of Dermatology

at Yale University School of Medicine

and Central Connecticut Dermatology,

Cromwell, CT

History:

Taylor’s problems started when she began noticing patches of scaly, flaky skin on her scalp, which slowly crept below her hairline. While her static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) score was 4 (severe disease), her body surface area (BSA) was only 5%, reflecting the fact that her psoriasis was confined to her scalp and forehead. She had consulted at least two other dermatologists before she made an appointment to see me, bringing with her a plastic bag full of various topical medications as well as prescription and over-the-counter foams and shampoos, all of which had failed to clear up her skin.

Sadly, Taylor’s psoriasis was causing more than just outward symptoms. She confided that her condition was affecting her ability to concentrate on both her course studies and during competitions as a member of her college swim team. The distracting nature of her psoriasis was taking her focus away from the goals she considered most important in her life.

Initiating treatment with a TYK2 inhibitor:

Despite no signs of any real improvement, none of Taylor’s previous physicians had suggested any treatment beyond topical therapies. By the time I first saw her several months ago, her frustration had manifested into a powerful motivator to try a new therapeutic approach. Because Taylor didn’t want to take an injectable biologic while she was still in school, I suggested deucravacitinib, a once-daily oral medication. I explained to her that it can be taken with or without food, had an excellent safety profile and doesn’t require laboratory monitoring. Taylor quickly agreed to begin treatment.

When I saw Taylor at her 8-week follow-up, her scalp psoriasis had improved by about 50%, which is where I expected her to be at that point. She was very pleased with the reduced itching and scaliness. Taylor’s skin showed vast improvements, and she didn’t experience any side effects (the most common ones include upper respiratory infections, acne and oral ulcers). In short, she tolerated the drug extremely well. Based on deucravacitinib’s results in clinical trials—versus placebo and the oral drug apremilast—I expect to see further improvements when I see Taylor again in a few months.

Considerations:

This case shows that not all patients who suffer terribly from moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis have a BSA of 10% or more, which was the cutoff for participants in the deucravacitinib clinical trials. If someone has a localized area of involvement—the hands, feet, genitals or, as in Taylor’s case, the scalp—where topicals have been ineffective, I would encourage the use of a systemic therapy like deucravacitinib. As physicians, we need to offer therapies that are highly efficacious, even though a particular individual’s BSA may be low. As Taylor can certainly attest to, the improvements in quality of life and self-confidence are immeasurable.

Q&A

Insight on managing plaque psoriasis

Avoiding triggers

Q: What are common psoriasis triggers and how can they be managed?

A: Certain medications are known to trigger psoriasis, such as antimalarials, interferon, beta blockers, angiotensin converting enzymes and lithium. On the other hand, the withdrawal of systemic steroids can be a trigger. Some of these are well-established triggers while others have only minimal negative impact on psoriasis, and, of course, the impact on psoriasis varies from patient to patient. It is best to avoid those medications when possible, but occasionally we have to treat patients with other psoriasis therapies to prevent a triggering medication from causing flares.

Perhaps the most common trigger is the reduction of sunlight that occurs in northern latitudes, particularly in the winter. While some patients rely on trips to sunny places, phototherapy or systemic therapies to maintain remission during long winters, we have many treatments to deal with psoriasis and are able to keep those patients clear throughout the year.

Strep throats are a unique trigger, most commonly of guttate psoriasis, which is a form of psoriasis in which patients break out in numerous small lesions shortly after a strep throat. Treating with antibiotics is effective for the strep but does not usually prevent guttate psoriasis. Occasionally, patients have benefited from tonsillectomy, particularly if they develop guttate psoriasis repeatedly following bouts of strep tonsillitis.

—Mark G. Lebwohl, MD,

Professor and Chairman Emeritus, Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, and Dean for Clinical Therapeutics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NYC

Easing the psychosocial impact

Q: What can help patients cope with the psychosocial aspects of psoriasis?

A: This is a really important question. One thing I do is address the elephant in the room and start by asking, “How do you feel about yourself? Are you in a relationship? Are you comfortable with sexual activity? With shaking hands with people? How can we help make this better?” So first, I acknowledge this is an issue.

Another thing I may encourage is going outdoors to get sunlight. When the weather’s nice, I say, “The sun can help your disease. Ten to 15 minutes of exposure is actually good for your skin.” Make it a positive thing, that something simple and even fun can help them manage their disease.

In addition, I advise patients to seek out support groups, specifically the National Psoriasis Foundation (psoriasis.org). And I sometimes suggest social media, as connecting online and seeing images of others with the disease has helped a lot of my patients feel less alone.

Finally, I provide hope by talking about all the breakthroughs in treatment. I tell them we have great options, and they should feel optimistic about coming to me now instead of 10 years ago. Some have been told there is no cure, and while that’s true, I emphasize there are ways to keep their psoriasis extremely well controlled.

—Seemal R. Desai, MD,

Clinical Assistant Professor of Dermatology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; founder and Medical Director of Innovative Dermatology, Plano, TX

Strategies to improve adherence

Q: What are common barriers to adherence, and how do you help patients overcome them?

A: Common barriers include cost and access to medication as well as general compliance issues. Lack of compliance could result from whether the drug is administered as a shot or a pill or from the frequency of dosing. It could be the patient thinking, if this is a chronic disease, will I need to take it forever? The idea of being on medication long term can discourage some patients from even starting it. During the COVID pandemic, there were a lot of concerns about immunosuppression and whether they should discontinue their medication.

To help patients through barriers, I provide individualized counseling. I like to spend time, talking to them and explaining the importance of adherence. I try to put myself in the shoes of the patient, which is very helpful. For example, if cost is an issue, I direct them to pharmaceutical patient assistance programs and the NPF website at psoriasis.org, which offers resources on getting financial aid and appealing insurance decisions. Most important, I talk about the long-term nature of the disease and explain what systemic therapy means. I try to focus on treating the disease and clearing their skin, and I stress that it takes sticking to the instructions for their medication and staying on the treatment plan.

—Seemal R. Desai, MD

Putting side effects into perspective

Q: Before prescribing a biologic, what patient education do you provide?

A: Some of the older biologic therapies, such as TNF blockers, include black box warnings about infection and malignancy, and all patients receiving biologics are asked to undergo annual TB tests. Counseling about these warnings is prudent, as it’s better that patients hear the facts from their physicians than read about them and imagine worse risks than what truly exist. And now that we have a non-live vaccine for herpes zoster and effective COVID, flu and pneumonia vaccines, many physicians recommend those vaccinations for their patients. While the newer biologics that block IL-17 and IL-23 don’t carry black box warnings regarding infection and malignancy, one of the agents has a mandated warning to counsel patients about depression and suicide, as there were four suicides among approximately 4,000 patients treated in clinical trials. The package insert warning clearly states that it is not known if the drug was causal in any of the suicides; nonetheless, patients have to fill out a form with the prescribing physician documenting that suicidal ideation and depression were discussed.

—Mark G. Lebwohl, MD

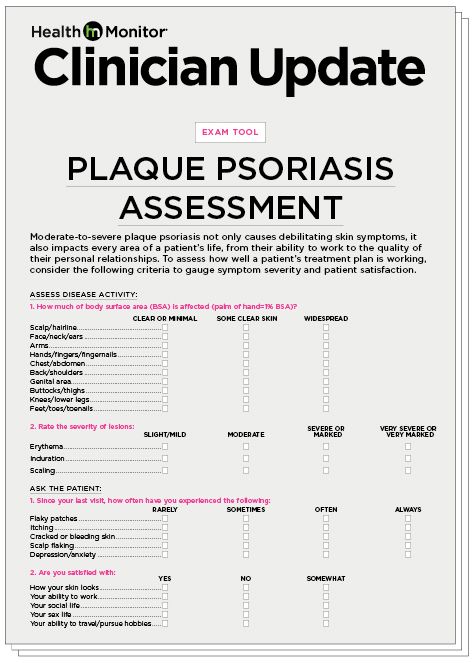

Plaque psoriasis assessment

Moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis not only causes debilitating skin symptoms, it also impacts every area of a patient’s life, from their ability to work to the quality of their personal relationships. To assess how well a patient’s treatment plan is working, consider the following criteria to gauge symptom severity and patient satisfaction.

Click here to download a printable version of the assessment tool.

Clinical minute:

Test your knowledge of plaque psoriasis treatment

Special thanks to our medical reviewers:

Tina Bhutani, MD

Co-director of the UCSF Psoriasis and Skin Treatment Center in San Francisco

Mark G. Lebwohl, MD

Professor and Chairman Emeritus, Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, and Dean for Clinical Therapeutics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NYC

Maria Lissandrello, Senior Vice President, Editor-In-Chief; Lori Murray, Associate Vice President, Executive Editor; Lindsay Bosslett, Associate Vice President, Managing Editor; Joana Mangune, Senior Editor; Marissa Purdy, Associate Editor; Erica Kerber, Vice President, Creative Director; Jennifer Webber, Associate Vice President, Associate Creative Director; Ashley Pinck, Associate Art Director; Molly Cristofoletti, Graphic Designer; Kimberly H. Vivas, Vice President, Production and Project Management; Jennie Macko, Senior Production and Project Manager; Taylor Wexler, Director, Alliances & Partnerships

Dawn Vezirian, Vice President, Financial Planning and Analysis; Donna Arduini, Financial Controller; Tricia Tuozzo, Sales Account Manager; Augie Caruso, Executive Vice President, Sales & Key Accounts; Keith Sedlak, Executive Vice President, Chief Growth Officer; Howard Halligan, President, Chief Operating Officer; David M. Paragamian, Chief Executive Officer

Health Monitor Network is the leading clinical and patient education publisher in dermatology and PCP offices, providing specialty patient guides, discussion tools and digital wallboards.

Health Monitor Network, 11 Philips Parkway, Montvale, NJ 07645; 201-391-1911; customerservice@healthmonitor.com.

©2022 Data Centrum Communications, Inc.

CED22-CU-PP-2OS